Pushing on a String

The ECB rate cut won’t do anything to solve Europe’s core problem

Central banking time! After last week’s review of Federal Reserve policies in the U.S., it’s time to check on the European Central Bank’s rate cut. Hope you find this interesting – let me know your thoughts in the comments section.

Please hit the “like” button, share, and subscribe! Your support keeps me going. Many thanks!

On June 6, the ECB finally pulled the plug. As widely expected at that point, the European Central Bank lowered its three key policy rates by 0.25% each. The deposit rate (the equivalent of the U.S. Federal Reserve’s IORB) was cut to 3.75%, the main refinancing rate (one-week loans from the ECB) to 4.25%, and the punitive overnight rate to 4.5%.

The ECB noted that inflation was still above the 2% target, and in written comments noted it expected inflation at 2.5% in 2024, 2.2% in 2025, and 1.9% in 2026. Core rates were even higher. But on balance the Eurosystem is a bit ahead of the U.S. in inflation fighting, looking at trajectory of prices.

Central banks control economic activity with their policy rates. Lower interest rates make borrowing cheaper for consumers and corporations and therefore stimulate spending and the economy at large. Economic orthodoxy says that central banks use interest rate targets to keep a delicate balance between growth and price stability.

And that’s exactly the core problem for the European Central Bank.

Growth in the Eurozone is abysmal

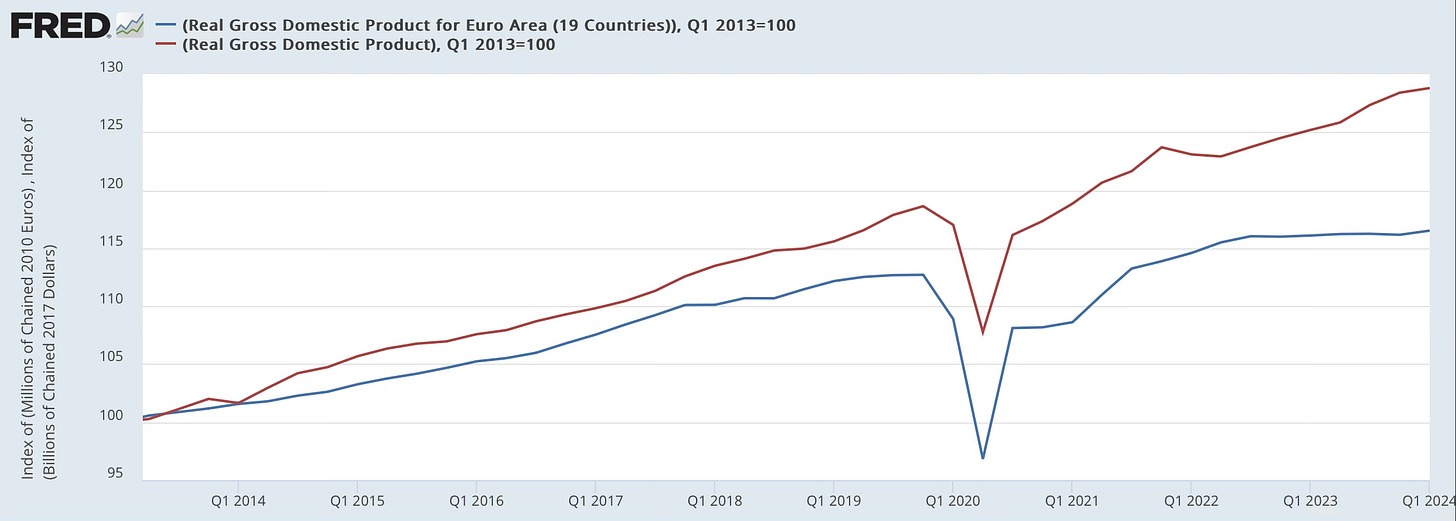

As the ECB pointed out, it expects economic growth to pick up to 0.9% in 2024, and to 1.4% in 2025. At those rates, the Euro area is falling behind the U.S., and the gap is widening1.

Here’s how the economies drifted apart over the last 10 years. In this chart, I indexed real GDP at 100 at the beginning of 2013 for both the U.S. and the Euro area. Please note it’s real GDP, i.e. removing the impact of differences in the inflation rate. Since 2013, the U.S. economy grew 12.3% more than the Euro-area economy. To put that into perspective: that’s an extra $7,000 per year in annual income on average!

Now, Europe is a large continent with many economies in different stages of development. But there’s little doubt there’s something like a locomotive at the center, geographically and economically. When Germany sneezes, Europe catches a cold.

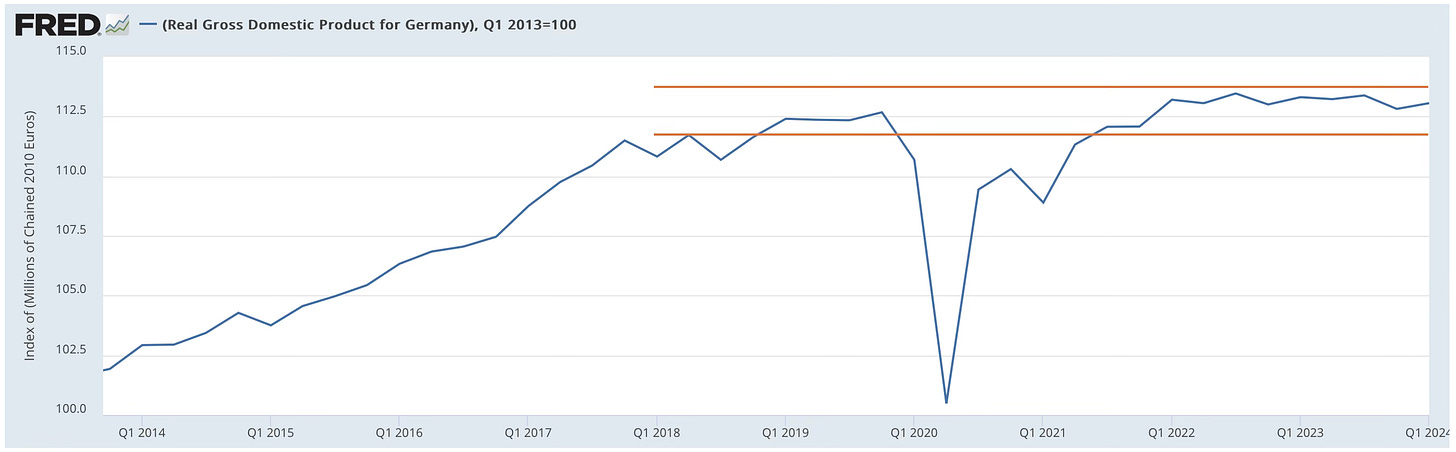

(Do flatlines count as a trend? German real GDP, indexed to 100 in Q1 2013).

We’re getting closer to the real problem of Europe. Essentially the German economy hasn’t progressed at allover the last five years2!

Germany is governed by a three-party coalition among the Greens, the Social Democrats, and the Free Democratic Party, an unlikely bunch, but necessary for a majority in the German parliament. It’s widely known now that the government has imposed a transition program on Germany to make energy generation greener. The two key features of this transition are:

There’s no agreement what “green” is. EU members like France and Sweden and even the EU taxonomy itself consider nuclear energy as green. Countries such as Germany and Austria disagree, and Austria has even filed a lawsuit against the EU to have the taxonomy changed.

It’s painfully expensive, and it’s unclear where the money is supposed to come from.

Not really the best starting point for such a large transformation.

And predictably, it left both consumers and corporation insecure about spending needs - consumption, rings a bell?

For home buyers and builders, the new energy laws will bring a massive rise in construction and renovation costs. Since January 2024, the law requires at least 65% of total building energy use to come from renewable sources for any heating systems being installed, irrespective if it’s new buildings or renovations of older homes. Considering a lifespan of heating systems of about 30 years, homes built until the mid-1990s with little thermal insulation and high heating energy needs will have to switch in the next few years, facing additional costs of 30-50,000 Euros for more expensive renewables. The default option will be heat pumps. But it is uncertain if the existing electrical grid can even support the new load. The grid is stretched so badly that operators have obtained an approval to shut down energy to heat pumps during demand peaks, which usually occur in winter, leaving Germans freezing exactly at the coldest times of the year.

The backlash against the next law was so strong that the minister for the economy, Robert Habeck, had to run it through parliament in several iterations over years, adding a complex layer of subsidies.

Subsidies were supposed to be paid from the government’s “Climate and Transformation Fund”, a special purpose vehicle. Where should the money for the fund come from? The government looked around and found an unused spending program from the covid time, worth 65 billion euros. Nice way to plug the gap, they thought. But the German federal constitutional court ruled that repurposing the covid relief fund was an illegal breach of debt ceiling rules. Financing for the Climate and Transformation Fund collapsed.

The question for consumers now is: Who is going to pay for their expensive heating systems? Little wonder that private consumption in Germany is anemic in the face of those uncertainties.

Corporations are looking at a similar stalemate. The government has long pushed industrials to adopt “green hydrogen” to replace oil and gas as energy carriers. Again it promised subsidies to finance the expensive transition, with money coming from the doomed transformation fund. Again, promises fizzled out.

Robert Habeck probably sees himself as the architect of a new German economic miracle. Like in the 1950s, when Germany rose from the rubble of war, this time Germany will rise, in Habeck’s vision, from the rubble of carbon-based energy. Large corporations will start investing, creating a virtuous circle of rising employment, consumer spending, and new prosperity.

(Habeck’s desperate media campaign. “Energy transition creates jobs”)

But corporations don’t work that way. Corporations invest to improve productivity. They embrace technologies which raise their competitiveness and make them stronger. The new energy sources aren’t anything like that. They are little tested (for a deep dive how long transitions have taken in the past you might want to read speed kills), tend to be more expensive, their long-term viability is unknown, and they make business sense only because of large government subsidies. Backlash from the industry is so strong that in late January 2024 Habeck appealed to “patriotism” to generate more investments. It was Habeck’s second break from central party dogma3 – a green party leader endorsing a vilified term such as patriotism?

Doubling down, scaling up

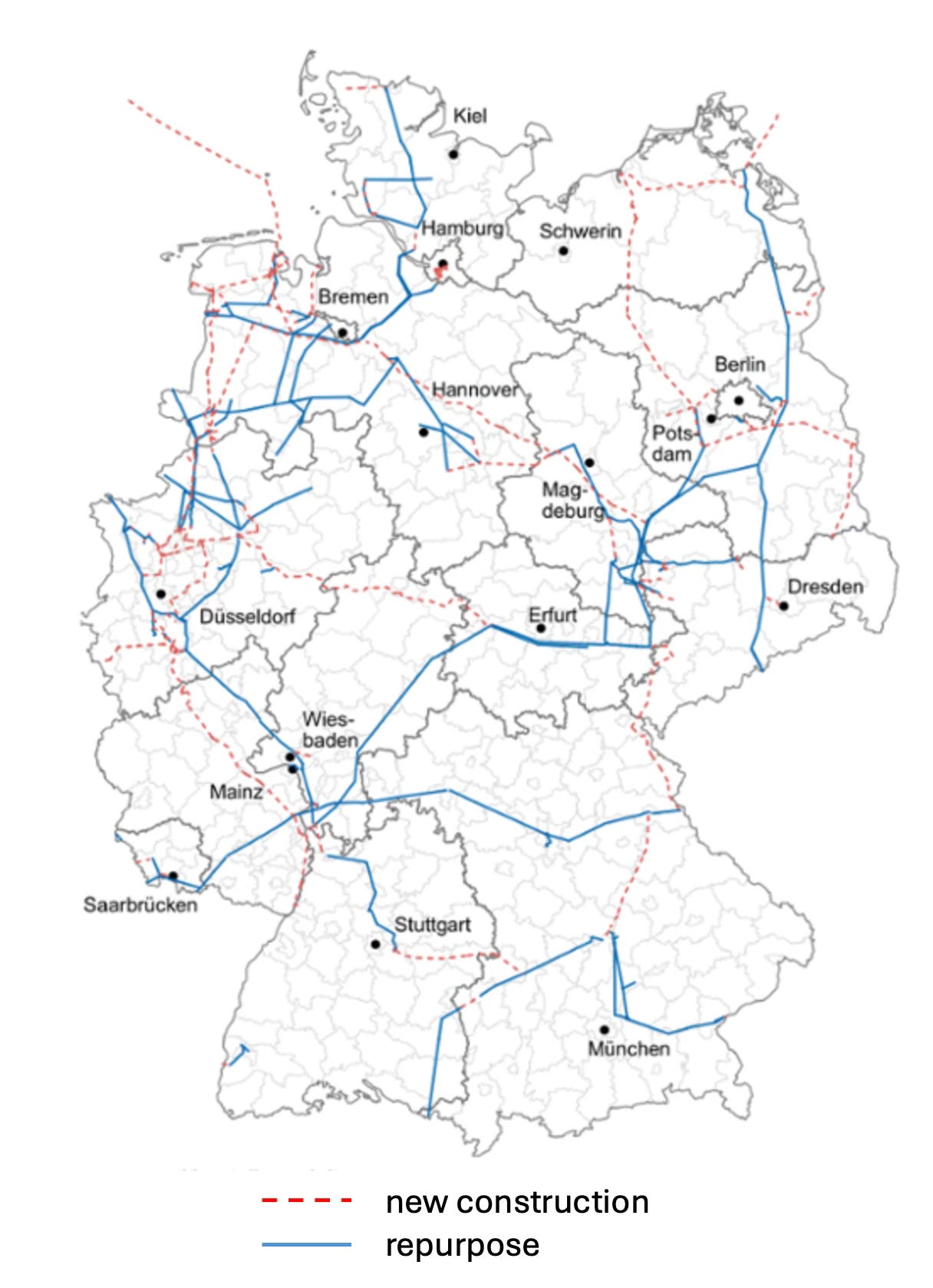

Where some people see risks, governments see opportunity – to double down with other people’s money. Having taken a big L for transition initiatives so far, the German government intends to launch an enormously expense, national hydrogen grid to supply green hydrogen to industry, replacing gas and oil.

The ministry for the economy and climate advertises on its webpages that the hydro grid will be embedded into the European hydro grid and use existing pipelines. Maybe a few items deserve attention which aren’t that clear from official documents.

A “European hydro grid” doesn’t exist. It will have to be created just like any German grid.

Repurposing existing gas pipelines sounds like an obvious thing to do, a pipe is a pipe, right? Well, no. Hydrogen has different chemical properties than natural gas. Gas is usually transported in steel pipes. Hydrogen however leads to embrittlement of steel, especially high-strength steel, making it vulnerable to cracks, failures, and leaks, and leading to a continued hassle with repairs and maintenance.

(The Brittle Brothers taking a critical look at Germany’s gas pipelines)

The standard approach to deal with this issue has been to mix hydrogen and gas, with a hydrogen share of not more than 20%. But this of course raises the question, why do it at all if you want to replace natural gas?

Conventional wisdom is that in the end it’s cheaper to rebuild hydrogen pipelines from scratch, even if the initial outlay is higher. The true economic costs of a hydrogen grid will be much more than advertised.

“We have to talk about suppliers”. Where is all that hydrogen supposed to come from? Germany can produce no more than 50% of what Habeck thinks the country will need, due mainly to the intermittency of wind and solar energy (hear, hear! I can’t believe they actually said it!). The rest will come from imports, from the North Sea, the Baltic, Southwest Europe, Southeast Europe, South Europe – you guessed it, from anywhere. Minister Habeck is busily traveling Morocco, Algeria, and Saudi Arabia to promote hydrogen deals.

The grandiosity of the scheme is reminiscent of another failed European megaproject, Desertec. The intuition behind Desertec was to generate PV energy in the Sahara Desert and transport it to Europe. Desertec was set up by a network of politicians, scientists, and economists which itself was founded by the Club of Rome, of all organizations. It was advised by an additional layer of governmental agencies. Pretty soon the foundation realized that transporting electrical energy over the large distances to Europe was technically quite difficult but politically even more challenging. Therefore, the project was reframed quickly as a large regional development project, with only the excess energy going to Europe.

The fate of Desertec was predictable. It involved a large number of politicians across many European and north African countries, none of them having a real stake in the project. The business case for the companies which actually had to put money on the table wasn’t much more than a vision and doubtful projections of energy consumption and energy prices many decades into the future. Desertec didn’t go anywhere.

Robert Habeck should take some cues from the fate of Desertec. Politically motivated grand projects are not known for strong governance structures. Governmental ministers can mobilize large quantities of money, but they don’t have accountability for a financial or broader economic return on that money. That leads to attrition and waste in the best case as it attracts profiteers and snake oil sellers, but also to fraud and corruption in the worst case. That’s not a marginal problem, as Germany should know. It just turned out that German companies paid more than €4 billion for Chinese emission reduction certificates which were issued fraudulently (UER are sold by companies which exceed emission reduction targets and bought by companies which are below targets. The mechanism is supposed to establish a “market price” for carbon emissions and monetary incentives to meet reduction targets).

Lack of accountability, weak governance, unclear decision processes, and a diffuse vision instead of a clear business case – all of that makes it very difficult to inspire confidence and fortitude of businesses and consumers. As Habeck continues on his lone crusade, he’s looking ever more like the mad scientist.

The ECB can play with policy interest rates all day long, but it won’t solve Europe’s underlying problem. The bloc’s key issue isn’t tight credit, but corporations and consumers in the largest member country are holding back in the face of huge uncertainties in the German government’s economic policies combined with regulatory overkill.

The government received a shot across the bow in last Sunday’s EU elections, where the Greens lost 9 of their previous 21 seats in the EU parliament. German national elections however are still more than a year away – unless the government gives in to public pressure and calls early elections, like Macron’s French government.

What do you expect, course-correction or a government crash? Curious to hear your thoughts!

All the best,

John

Eurostat, Real Gross Domestic Product for Euro Area (19 Countries) [CLVMNACSCAB1GQEA19], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Real Gross Domestic Product [GDPC1], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

Eurostat, Real Gross Domestic Product for Germany [CLVMNACSCAB1GQDE], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

The first large break from green party dogma was in February 2022. Germany was reviewing its energy strategy after the Russian invasion of the Ukraine, and Habeck appeared to be open in a TV interview to extend nuclear power generation. However he was sabotaged by his own state secretary.

Two things which are mutually exclusive. Climbing down the energy density ladder while climbing up the human flourishing ladder.

Great thoughts. This is the equivalent to putting a bandaid on something that needs surgery. =]