Speed Kills

If wind and solar energy can’t sustain the power grid, why are they called “sustainable”?

I have long admired the car industry. For me, the car industry is the epitome of industrial development. A car factory easily churns out two hundred thousand cars a year, and those cars run over years through rain, sunshine, snow, storms, freezing temperatures, and heat waves with very little maintenance. It’s beyond my comprehension how it’s possible to produce those large numbers of complex machines with such precision and quality.

The industrial production of cars has gone through an evolution over more than one hundred years since Henry Ford started mass-producing the Ford Model T in 1908. During that time, quality and durability improved. Fuel efficiency became better. Safety features like seat belts and airbags were introduced.

The industry grew in an ecosystem of supporting industries. As cars were more widely adopted, the production of fuel increased, and a distribution network was built. Engineers, politicians, and regulators have had one hundred years to understand the operational complexities, challenges, and risks of that industrial ecosystem. Today we know how to deal with them through the lifecycle of the product.

In fact, the symbiotic relationship between the car industry and oil industry is representative for the industrialization of society. Societies organized around a dominant carrier of energy and adjusted workflows in production and personal life around it. As economies grew and industrial output increased over time, the dominant carrier of energy became more deeply imbedded and more difficult to substitute.

When James Watt patented an improved steam engine in 1769 which ultimately kicked off the industrial revolution, the dominant energy sources were wood and charcoal. You would think that for industrial purposes, coal was going to take over quickly from wood – after all, the 19th century is often characterized as the age of coal industry. But it took coal until the end of the 19th century to become the new dominant source of energy in western countries. In the Soviet Union, it took until about 1930, and in China, until 1965.

Once coal had reached dominance, it didn’t yield quickly to its successor, oil. Even though oil was available in sufficient quantities and processes to refine and use it were well known in the early 20th century, people stuck to coal which was the largest energy source, providing more than 50% of all energy used. It took oil until the 1960s to overtake coal. Counterintuitively, over the 20th century coal was the single most important energy source, not oil.

A third transition started later in the 20th century, when natural gas gained a larger footprint. Gas became the dominant energy source in the Soviet Union during its final years, and in the U.K. at the end of the century. It will be interesting to see if natural gas can complete its transition cycle in other countries, because political decisions are endorsing renewable sources of energy today.

Resource analyst Vaclav Smil found some very interesting dynamics in the substitution cycle. Transitions from wood to coal, from coal to oil, and from oil to gas all followed the same pattern. Each transition took about 60 years from the time it became a notable but small source of energy (which Smil put at a 5% share) until it reached a share of 50% of total production. As Smil points out, that’s two to three generations of people.

So it’s a fair question now: why didn’t those transitions happen more quickly? The advantages for switching from coal or oil to gas are quite obvious, aren’t they? As I’ve pointed out in a previous posting (Peak Panic), when I grew up in a mountain town in the 1970s and 1980s, for months in winter you could not see across the valley because of a thick layer of smog, mostly from heating homes with coal. It was an obvious health hazard. Burning coal releases sulphur, smut, carbon dioxide, and who-knows-what other particles and compounds. In comparison, burning gas releases none of that dirt but carbon dioxide – bad enough, but still much better.

To replace an existing technology, it’s not just sufficient to rip out old ovens and furnaces and swap them for new ones. You’ll also have to deal with the logistics of an energy carrier through the whole supply chain: how to procure it and distribute it, how to handle it in a save way, what to do with the residue. All that needs to be done at scale. That’s precisely why any given any carrier became dominant in the first place: because a society learnt how to deal with it at scale, making it efficient.

Breaking the pattern?

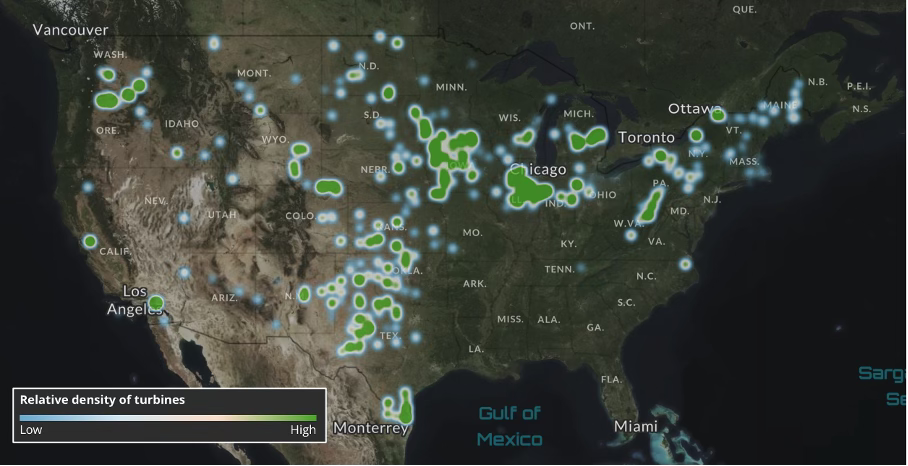

We are now in a transition which is accelerated because of political decisions. This time, fossil fuels in general are being substituted by renewable sources. Wind and solar energy are pushed into production in western countries and have achieved an impressive theoretical contribution to overall electricity supply. Texas, which is the leading wind energy producer in the U.S., now has an installed wind capacity of more than 40,000 MW, versus a peak recorded demand of 85,000 MW (Saturday August 20, 2023; all-time weekend peak). Keep in mind the average yield is around 30%-35% of installed capacity, so Texas can generate around 15,000 MW. In Germany, the contribution from wind exceeded coal energy (domestically produced) in 2023 for the first time. On the face of it, that’s a pretty quick turnaround.

(Heat map of wind capacity in the U.S.1)

But as capacity is ramped up much more quickly than in previous episodes of substitution, it shows that politicians missed out on the learning curve and haven’t understood the complexity on transitions over the complete lifecycle. This can lead to unexpected, but nevertheless severe problems.

Take wind turbines. The towers are usually made from steel, which is easily recyclable. But the blades are made from composite glass or carbon fiber. They are up to 260 ft long and weigh in at 36 tons. What do you do with them once they are out of service? Turns out, nothing, quite literally. The blades are cut into smaller pieces just to transport them and then deposited. At the moment there is not a single meaningful use case for spent blades. A company called Global Fiberglass Solutions thought up a process to grind up the blades and recycle them into pallets and floor panels, but it’s already gone bankrupt. Looks like the business proposition wasn’t that sustainable.

(Lotta energy, lotta waste: used wind blades at the yard of defunct processing company Global Fiberglass near Sweetwater, Texas)

(Thousands of used wind blades stacked near Newton, Iowa)

Bloomberg NEF (New Energy Finance) calculated that in 2020 and 2021 alone, wind blades consumed 20% of the total space allocated for all construction and demolition material deposits. The deposits are so large it was easy to find them in a quick search on satellite images.

Unfortunately, the waste issue will be compounded by two structural drivers: the massive growth of wind capacity in recent years, and a much lower lifespan than expected. Wind towers were built for an expected life of about 25 years. However, as the industry gathers experience at a broader scale it turned out that turbines last for only 7-10 ten years, and blades have a shorter life as well.

Similarly, solar panels are aging more quickly than expected. They were designed for a lifespan of 20-25 years, but in reality it comes down to 10-15 years because both of the main components of the current installed base are failing: Inverters which turn DC current, which solar PVs produce, into AC current, which is used in the electrical grid. And new research from Australia2, a country supposedly predestined for solar energy production, shows that panels age faster than expected, ironically due to increasing temperatures. The degradation is highest in areas of high temperatures and high humidity.

Like wind blades, used solar panels currently end up in landfills because there’s no meaningful technology to recycle them. The International Renewable Energy Agency (“IRENA”) projected that until 2050, solar PV waste will amount to 78 million tons, agreeing that this is a huge environmental problem. However that projection is based on a 30-year lifespan. As the actual lifespan is shorter, the problem will be even worse. IRENA claims that waste is a valuable resource, and that “ … the institutional groundwork must be laid in time to meet the expected surge in panel waste. Policy action is needed to address the challenges ahead, …”.

Take note of the words used: institutional groundwork must be laid, policy action is needed. It shows just how much wishful thinking underlies the transition.

The fast-track, politically ordained transition is creating another problem, the intermittency of production. Let’s take a look again at the experiences of frontrunners Texas and Germany.

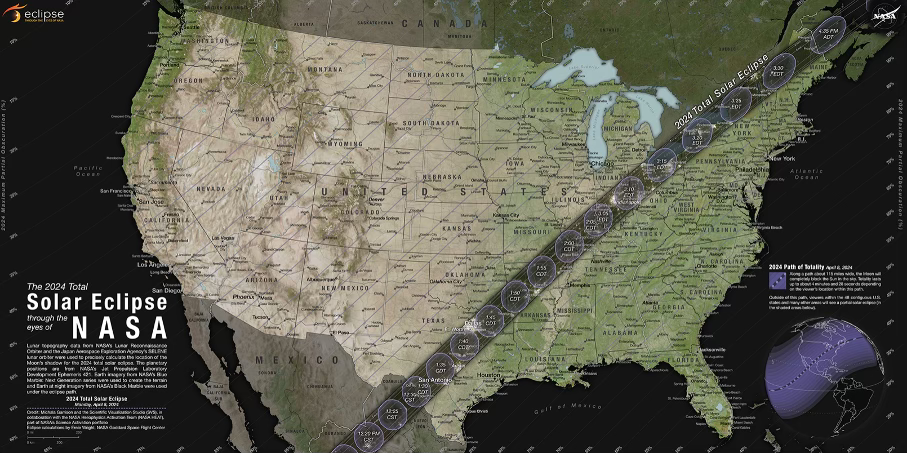

Texas is not only a leader in wind energy, but also solar (it’s the second-largest producer of solar energy in the U.S. after California). On April 8, 2024, large parts of the U.S. experienced a spectacular cosmic event, a full solar eclipse. The sun was blocked out in a corridor right across Texas until the northeast of the country.

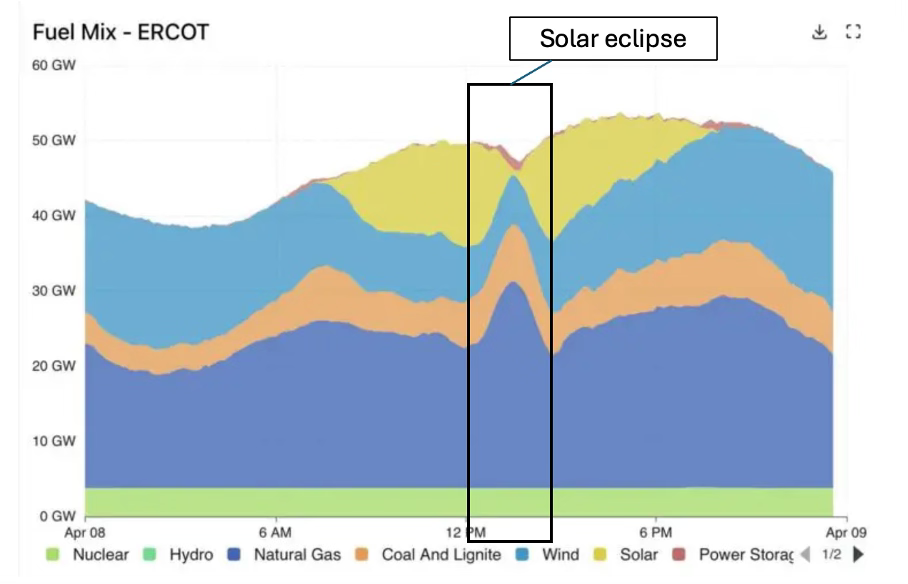

The eclipse took place in the early afternoon, right at the time of peak production of solar energy. Fair question, how did solar energy do at this time? According to data from ERCOT (Electric Reliability Council of Texas, a grid operator which serves 90% of Texas), the impact on solar generation was pretty dramatic.

Solar energy provided more than 10 GW of electricity during daytime but dropped to almost zero at the peak of the eclipse. Natural gas had to bail out the grid, with a residual gap caught by battery energy storage systems operated by Tesla.

Take note also of wind energy: despite an installed capacity of more than 40 GW, wind never contributed more than 15 GW. Why are solar and wind called “sustainable sources of energy” if they can’t sustain the grid?

In Germany, government ministers high-fived each other when the production of renewables exceeded fossil fuels for the first time. They failed to mention a key fact: they were talking about domestic production only. As Germany is shutting down domestic producers, the country has become dependent on foreign producers, which made it a threat to the stability of European grids. Germany imports energy from neighbors like France and the Czech Republic, both of which are expanding their nuclear generation capacity. Adding back foreign-produced energy, coal is still larger than wind energy. The German grid has become so vulnerable that the government passed new regulations which allow grid operators to cut energy going to heat pumps and EV charging, precisely the technologies which were supposed to drive Germany’s energy transition. Can it get even more absurd? (More details on this here).

Energy transition to cleaner sources is desirable and has been beneficial in the past to eradicate smog in cities, prevent deforestation, and even helped the survival of species (when crude oil replaced whale oil as the primary source of home lighting). But the same past experience has shown that transitions take time until the complex interactions of economic agents and systems adjust. In the current phase of substitution, new energy carriers basically piggyback on existing sources. As first evidence from the transition on a large scale comes in, it turns out that the resource intensity to set up renewables has been underestimated (much shorter use cycles), and external effects have not been considered at all (enormous waste quantity). Current public policies with accelerated transition goals have become a threat to energy security, to the responsible use of resources, and support of the broader population.

Curious to hear your thoughts!

all the best

John

The U.S. Wind Turbine Database

Accelerated degradation of photovoltaic modules under a future warmer climate, Shukla Poddar, February 14, 2024

Excellent article John. You clearly articulated the reality of the pace at which each transition from one energy node to the next improved the size and efficiency of the complex system supporting human flourishing. One of my favorite quotes comes from Doomberg “in the war between platitudes and physics, physics stands undefeated”. The problem, as you point out, is we have lived in an ever higher energy density bubble for the last 200+ years, coupled with simultaneous ever increasing pace of technological innovation, has created a type of blindness to where this abundance comes from.

For the majority of first world inhabitants, electricity comes from a magic hole in the wall, food comes from supermarkets and the ability to travel vast distances comes from a fuel pump. We live in an age of widespread magical thinking in which every problem has a cheap technological solution, if we just think hard enough about it. Our political class have become the primary adherents to the school of magical thinking, with economic models that completely divorce economic growth and cheap and reliable energy as symbiotic dependencies. In this world you can simultaneously climb down the energy density and reliability ladder while climbing up the economic prosperity ladder. Even better, you can spend yourself rich while doing it.

Thanks to folks like yourself, Robert Bryce, Michael Shellenberger and others, trying to ring the alarm bells about the need for long term strategies to solve the current and future energy and environmental challenges. Keep up the great work.

If I might follow your excellent article an Corey’s great comments, the quote from IRENA that “ … the institutional groundwork must be laid in time to meet the expected surge in panel waste. Policy action is needed to address the challenges ahead, …”. shows the incompetence runs deep in the sustainable community. Systems Thinking would insist that all aspects of the full energy system should have been understood and acknowledged at the start, not after an expected surge (which was miscalculated by at least a factor of 2). Instead, these inconvenient truths were hidden or ignored in the rush to implement these solutions. Policy driven decisions are rarely sound. Policy decisions based on ‘existential crises’ based, emotionally driven public support have almost no chance of creating a solution that is feasible and effective over the long term. We should be learning from this colossal failure and consumption of $Trillions and putting in place both leadership and laws to restrain this from happening again. We could have done much better if calm voices and clear thinking were allowed to address the issue.