Peak Panic?

As the momentum in climate activism reaches a turning point, a bombshell report reveals that Germany was cheated in its decision to shut down the nuclear power industry.

On a personal note, many thanks to my readers for their continued interest, and welcome to my new subscribers! I noted another strong uptick in page views as this publication continues to gain traction. I remain committed to delivering new research and insights to you.

I grew up in a small mountain town, as many of my readers probably know by now. Our house was at the southern side of the valley where the hills started sloping up from the valley bottom – ever so slightly you wouldn’t notice the gradient on a walk into the city center, which was just fifteen minutes away, but still enough to put my room above the roofline of the other buildings behind an old railroad track.

Because of this, from my room I had a truly majestic view over the city and up the mountain range which towered over it on the north. That is, in theory. Because at that time, in the 1970s and 1980s, a thick blanket of smog covered the city for four or five months every year. Seen from my room, the few, isolated taller buildings near the city center faded in shades of grey, but the northern end of the city was blacked out. I don’t remember if you could even see lights at night.

The vista was even worse from the mountains. It looked like a grey puddle of ooze had spread out across the valley.

It was a time when the preferred energy source for heating was coal. Most apartment buildings didn’t have central heating, but coal ovens in the kitchen and the living room. When residents loaded coal bricks into ovens from the early morning, black smoke rose from chimneys without any filtering.

Forty years later, nothing is left of that kind of pollution. The air is clear all year round, even though many more people life there. It simply made sense to clean up. Houses were converted or rebuilt with central heating, switching away from coal to other energy sources and adding exhaust filters. Targeted regulation forced car manufacturers to equip cars with catalytic converters.

Those investments were costly. Selling cars with catalytic converters is more costly than selling them without. Complex filter technology for industrial purposes is much more expensive than simply building high chimneys to blow the dirt away as far as possible. But economic growth made it possible. GDP today is more than three times higher. The growth of incomes more than offset the costs of cleaner energy.

But apart from the visible air pollution, scientists also raised an alarm on increasing emissions of greenhouse gases. It's easy to forget, but climate change was a big topic already in the late 1980s.

(You know it’s a cultural phenomenon when goofy movies like Hot Shots, a 1991 comedy, pick it up in the climactic peak of the movie (no pun intended)).

Global warming really picked up in public attention in the 2010s as a key threat to the planet and to mankind. In 2015, the UN brokered an agreement among many UN member states on a number of policies to contain global warming. As negotiations were held near Paris, the agreement became known as the Paris Agreement. The aim of the agreement was to keep temperatures from rising more than 2° Celsius above pre-industrial levels. From the simulation models which were used to determine the Paris targets, it followed that by the year 2030 greenhouse gas emissions must be reduced by 43%.

Sensationalist reporting and fear-mongering escalated in the years which followed. My personal favorite is a 2018 article of Harvard Professor James Anderson, a researcher in atmospheric chemistry. Anderson concluded from his research that “the chance that there will be any permanent ice left in the Arctic after 2022 is essentially zero”1.

When the Paris Agreement was ratified, it had a long-term outlook. The year 2030 seemed very far away, so leading politicians felt comfortable signing up to ambitious targets. Worst thing to happen, they were not going to be in office anyway, so it was an easy decision to score voter points and leave the mess to their successors. The world, on the face of it, had aligned on climate goals.

United we stand! United …. on what?

Albania is a small country of fewer than three million people. It’s located north of Greece, and west of North Macedonia (still with me?) on the Mediterranean Sea. Not unusual for ex-communist countries, thirty years after the fall of the Iron Curtain it still far lags Western Europe in economic development with a per-capita GDP of just around $7,000, that’s no more than 14% of German GDP and 9% of U.S. GDP.

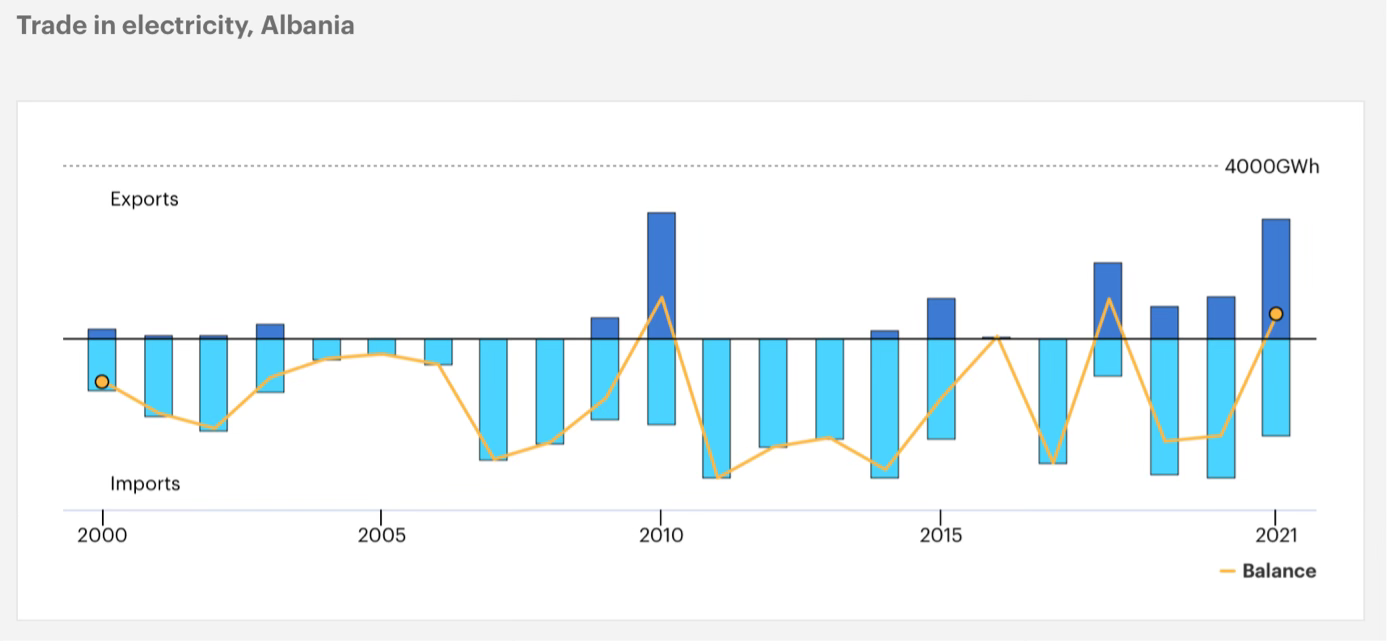

In 2019, Albania became the unlikely battleground for another global proxy war for energy. The country draws more than 40% of its energy use from oil and about 10% from coal. Electricity makes up around 30% of energy consumption. Albania is a mountainous country, and basically all locally produced electricity comes from hydropower. But electricity demand has been rising, and Albania had to import electricity in most years even though there is huge untapped local potential.

(Source: IEA International Energy Agency)

In 2019, the government announced plans to construct additional hydro power plants on the Vjosa, a river which originates in Greece. It is one of the poorest regions in one the poorest countries in Europe. Local environmentalists were undeterred. They enlisted Hollywood A-lister Leonardo Di Caprio, well known for his climate activism, to protest and fight against the plants.

Suddenly, it seemed, clean energy wasn’t the world’s biggest problem. As Leonardo Di Caprio pointed out, dams block the natural flow of water and sediment. And anyway, the benefits of hydropower were overstated. Impressed by the strength of those arguments, Albania’s government shelved plans for clean energy.

Albania might seem like a small country, but the conflict over priorities is emblematic for much larger parts of Europe, or other global regions. Divisions over climate change are moving much closer to Europe’s center of gravity. To decarbonize its economy, France has an ambitious plan to expand nuclear power. Finland’s Green party endorsed nuclear power as a clean energy source. And in the European Commission’s taxonomy, nuclear power is considered renewable. Austria on the other hand is a fierce opponent of nuclear energy and filed a lawsuit against the European Commission for the taxonomy.

In the past, all that was largely an ideological battle.

It was fought among lawyers and bureaucrats, and carried out on the back of countries many people don’t even know they exist.

But now, the chickens come home to roost. Germany, the country on the most progressive track for energy transition, provides an interesting case study.

Under experimental energy policies, Germany had developed a lopsided dependency on Russian natural gas. Cheap Russian gas helped stabilize German electricity bills for a while, but prices escalated after Russia’s invasion of the Ukraine.

(Household bills for electrical energy, Euros per month. Source: Statista)

Right at the time when prices started exploding, Germany nevertheless decided to go ahead with shutting down its remaining nuclear power stations. Wasn’t this madness? How did the decision come along? German newspaper Cicero asked the government to hand over meeting protocols according to the German Environmental Information Act. The government declined, which just nourished suspicions that the government had something to hide. Probably the decision wasn’t as clear-cut and unanimous as the government pretended it was. When Cicero sued the government and finally received documentation for the shutdown of nuclear plants, it turned out it was even worse2.

The chain of events which unfolded inside the German government after Russia’s invasion is nothing but outrageous, and a textbook example of what some might call “deep state intervention”. At the center: a government official heading the Nuclear Safety department at the Ministry of the Environment, a state secretary at the Ministry of the Economy, both of them die-hard opponents of nuclear energy, and an outsmarted minister.

Events kicked off at a TV interview with Robert Habeck, Germany’s minister for the economy, in the first few days after the invasion of the Ukraine. Would he consider extending the operation of the remaining nuclear plants (which were scheduled to shut down shortly)? Habeck answered defensively, but with a side remark that raised some eyebrows. He confirmed it was indeed a relevant question, and he would not decline solely for ideological reasons.

That was a big thing. A leading Green party representative who was potentially not aligned with a central party dogma?

Officials at both the ministry of the economy and ministry of the environment immediately asked their subject experts to prepare reports on the German nuclear plants: were they ready to extend their life, and under which constraints? Both working groups independently confirmed that a continuation was technologically feasible, safe, and economically preferable. In particular, the studies pointed out that the nuclear plants were going to provide much cheaper energy at a time when prices were rising exponentially.

The working group in the ministry of the economy passed on the report to state secretary Patrick Graichen, a direct report and confidant to Minister Habeck. That’s where the track ends. The report most likely never saw the light of the day.

The other working group, at the ministry of the environment, sent their report to Gerrit Niehaus, a lawyer who headed the Nuclear Safety department at the ministry. Niehaus, a strong opponent of nuclear power, must have been deeply upset about the endorsement and rewrote the central conclusions, as a side-by-side comparison shows, falsely concluding that the extension was not advisable due to safety considerations. Niehaus passed on his doctored report to his buddy Graichen, Habeck’s confidant, who didn’t hesitate to recycle it into yet another, even more egregious document. Graichen sent his pamphlet back to Niehaus who freaked out on the level of falsehoods in it and warned his own supervisor, writing in e-mail that conclusions were “…. in particular in the introduction grossly wrong. I tried to prevent the worst. (….)”.

But it was too late. Graichen had sent his report to Minister Habeck already, for whom it became the basis of all follow-up actions and documentation.

The revelations show that party dogma was driving decisions much more than technological and economic rationale, but also that there is actually much less conviction behind some of the central policies in the energy transition than what had been propagated. Even the priority ranking of goals is fluent.

Breaking the line

Against this background comes another challenge. Time to comply with the ambitious Paris Agreement targets is quickly running out. Remember, the agreement was ratified in 2015, with many years to go. But today, with less than six years left, many countries are far behind a 43% reduction of greenhouse gas emissions, despite considerable and extremely expensive efforts in some of them.

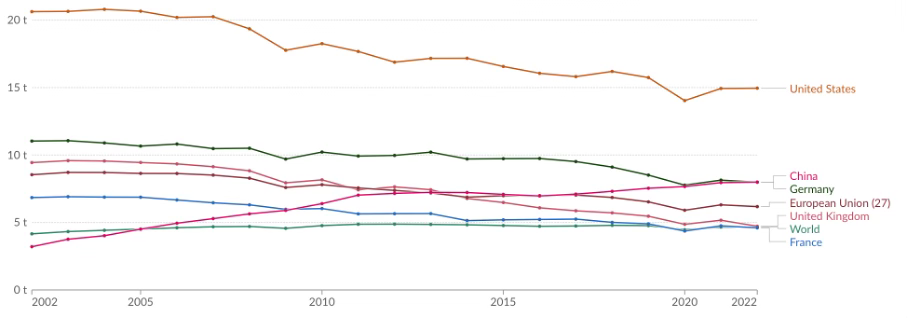

(Per capita CO2 emissions from fossil fuels and industry)

What to do next? Crank up the effort in a heads-against-the-wall approach, or adjust plans?

Scotland has broken the line already. Màiri McAllen, the Scottish net zero secretary, confirmed on April 18 that her government was abandoning the 2030 target and, importantly, would drop legally binding annual targets on reducing carbon emissions. Scotland will re-phase a plan with a 2045 target.

In Germany, Volker Wissing, the transport minister, made international headlines with a threat to impose a weekend driving ban, which he considered unavoidable to comply with the German climate protection law. Wissing wasn’t really serious about his threat. But it demonstrates to which extreme measures governments would have to go to now, and which certainly won’t be supported by the general population. Wissing’s message wasn’t directed at the population, but at the green faction in the coalition government which still blocks adjustments to the timetable.

The revelations in Germany are a huge scandal, the full scale of it still having to sink in. Robert Habeck was ordered to appear before lawmakers, and the news will be a severe test for the Green’s credibility and Habeck’s career. But they will probably accelerate another kind of transition, as they will force a new kind of dialogue: away from dogma and fear-mongering, and towards more balanced and outcome-oriented policies.

The tide in public discussion is turning. I guess when we look back in a few years to the early 2020s, it will very likely be seen as the period of peak panic. In Germany, the country most steadfast in energy transition and anti-nuclear policies, the conservative parties CDU and CSU have already announced to bring five of the six intact nuclear reactors online again if they get into government.

Let me know what you think,

Regards,

John

“We Have Five Years To Save Ourselves From Climate Change, Harvard Scientist Says”, Forbes, Jan 15, 2018

“Wie die Grünen beim Atomausstieg getäuscht haben“/ “How the Greens Cheated at the Nuclear Exit”, Cicero, April 25, 2024

thanks Don for the restack!

It will be some future government's problem indeffinetly. Change will happen when the low carbon options are cheaper and perform better. I just don't see anyone wanting to scarafice.

That was a puzzling decision to shut down the nuclear power right then. It may be a big factor in a struggling German economy that is much needed to hold off Russia.