Ottoman Empire

The fall of Syria will change global energy flows

Dear readers,

This is supposed to be the quiet time of the year, but geopolitical events have actually accelerated a lot. The Assad regime in Syria, a dynasty which had controlled the country for 6 decades, suddenly collapsed which was even more surprising than the series of government changes in Western Europe, which says a lot.

There’s still a lot of smoke on Syrian battlefields, too many actors, great uncertainty. But the implications are huge. The fall of Syria might very well mark a reordering of global energy flows. There’s a clear winner waiting for the dust to settle, but it’s not who you think it is.

I spent a lot of time digging out data and connecting the dots - hope this posting is interesting and helpful! Please leave a ‘like’ and let me know what you think!

The South Pars/ North Dome gas field is the world’s largest gas field. It spans a surface area of 10,000 square kilometers in the Persian Gulf and contains an estimated 1,300 trillion cubic feet (TCF) of natural gas, or 221 billion barrel-of-oil equivalents (BOE). 6,000 square kilometers and 800 trillion TCF belong to Qatar under the name North Dome, the rest to Iran under the name South Pars.

To put the size of the gas field into perspective: it is about three times the size of the Marcellus shale gas field in the U.S. and holds about 20% of the world’s total proven reserves1.

The Persian Gulf is rather shallow with a water depth of 65 meters in that region. The gas field is 3 kilometers underneath the seabed.

(Source: Oxfordenergy/ THE ECONOLOG)

Qatar exports gas through pipelines to its neighbors UAE and Oman, but much larger volumes as LNG. Qatar long was the world’s largest LNG exporter, but when Russian exports to Europe declined by two thirds in the wake of the war in Ukraine, U.S. exports to Europe tripled and made the U.S. the global #1.

But Europe isn’t the world’s growth theater; it is in Asia. Global gas demand is expected to rise from current 400 million tons per year (mtpa) up to 600 mtpa in 2030, driven largely by Asia. The U.S. will have doubled LNG export capacity by that time, but Qatar plans to raise output from North Dome by almost 100% as well, from 77 mtpa to 142 mtpa until 2030. It is geographically closer to Asia and has another huge advantage: it is the global lowest-cost producer, at only $0.3/ MMBtu, vs. a global average of $3-5. Even though demand is rising, competition will be heating up.

Turkey

Turkey has long been Europe’s passageway into Asia. Already Alexander the Great passed through Turkey to build the world’s first empire, and even one thousand years before that, one of the best known mythological wars, the siege of Troy, took place in Turkey.

But Turkey has quietly been building a new kind of passageway, a network of connections to large energy producers.

TurkStream, a pipeline connecting northwestern Turkey with Russian gas fields Urengoy on Siberia’s Yamal peninsula (home to a huge LNG terminal which was used to by-pass the NordStream pipeline) and Yamburg just across. Urengoy is the world’s second-largest standalone gas field after North Dome/ South Pars; Yamburg the third-largest. TurkStream was commissioned in 2020 and replaced another project called SouthStream, which was supposed to connect southern Russia and southeastern Europe2

BlueStream, a gas pipeline, like the younger TurkStream crossing the Black Sea

BTC oil pipeline (Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan), connecting the Caspian Sea, one of the most resource-rich regions, with a terminal in Turkish port Ceyhan

Tabriz-Ankara gas pipeline between Iran and Ankara

Kirkuk oil pipeline between northern Iraq’s oil fields and Ceyhan

(Oil and gas pipelines into Turkey from several of the Earth’s most resource-rich regions. Turkey connects gas to southeastern Europe, Greece, and Italy (via TAP/ Trans Adriatic pipeline))

That infrastructure was essential for keeping energy supply to Europe intact during times of political stress. When Russia first shut down the NordStream pipelines for ‘maintenance’ temporarily during the war with Ukraine, and the pipeline was sabotaged later, exports to Europe via TurkStream went on without interruption.

(TurkStream remained a key source of Russian gas for Europe when NordStream was sabotaged. Source: Statista)

Similarly, the Kirkuk pipeline stayed in operation during the time of sanctions against Iraq in the 1990s. Iraq kept exporting several hundred thousand barrels of oil a day to Turkish port Ceyhan in violation of U.S. and U.N. restrictions (actually I’m working on an adventure story related to that episode right before the Iraq war – if you know an agent who might be interested please let me know!). The oil went on Panama-flagged tankers which mostly sailed to the U.S. gulf coast.

Syria

The crown jewel however was missing – Turkey was cut off from both Saudi Arabia and more importantly from Qatar by a belt of hostile countries: Iran, Iraq, and Syria. It wasn’t that much of a problem for Saudi Arabia which exports oil, and for which there is an efficient infrastructure for transport in place. But for gas, pipelines are a huge improvement for transport compared to LNG, because the 2-way process of liquefaction is a wasteful and inefficient process.

In 2009, Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani, who ruled Qatar at that time, said, “We are eager to have a gas pipeline from Qatar to Turkey”. The route required the cooperation of Syria. It was the only option – Iraq was unthinkable during that time. The country was just emerging from the insurrection, but ISIS was already in formation. But Bashar al-Assad, Syria’s president, declined. Al-Assad was an ally to Russian President Putin, who later bailed his family’s rule out during the Arab Spring revolutions. At that time, Russian-German pipeline NordStream 1 was under construction; it went into operation in 2011. Any competing pipeline would have cut into Russia’s influence on Germany. A pipeline from Qatar was a no-go for al-Assad. Syria remained an obstacle for Turkey.

The attention of Syria’s key ally, Russia, was increasingly absorbed by the war in Ukraine which required an ever larger mobilization of resources and military forces. But an end to the war was on the horizon. President-elect Donald Trump repeatedly said he wanted to finish it as soon as he took office. Turkey probably realized there was a window of opportunity, but it was closing. Once the war in Ukraine was over, Russia was going to refocus on other areas under its influence.

Syria had been destabilized in the Arab Spring. While the Assad family regime survived, Bashar al-Assad had trouble keeping the country together as Syria became a proxy battleground for global and regional conflicts. Parts of northern Syria were under the control of Turkey, and Turkey launched several military operations in Syria against ISIS and Kurdish forces. Turkey also supported opposition forces like the Free Syrian Army (FSA) and the Syrian National Army (SNA), both formed by defectors from the Syrian military. Those armies were the key drivers of the rapid advance in early December towards the south of Syria and to Damascus. They met only weak resistance of surprised and demoralized government forces and toppled the government in a few days.

Four-Seas Strategy

The fate of Syria is uncertain. The coalition which brought down the Assad regime includes military factions like FSA and SNA, the powerful jihadist group HTS (Hayat Tahrir al-Sham), and other groups with varying ideologies and international backers. There’s a chance they might stabilize the country, in particular as they aren’t fighting an occupying force like in Iraq 20 years earlier. That scenario gives Turkey an opportunity to implement a strategy which, ironically, Syria’s Bashar al-Assad formulated fifteen years ago: the Four-Seas strategy, creating a new energy hub connecting the Black Sea, the Caspian Sea, the Persian Gulf, and the Mediterranean.

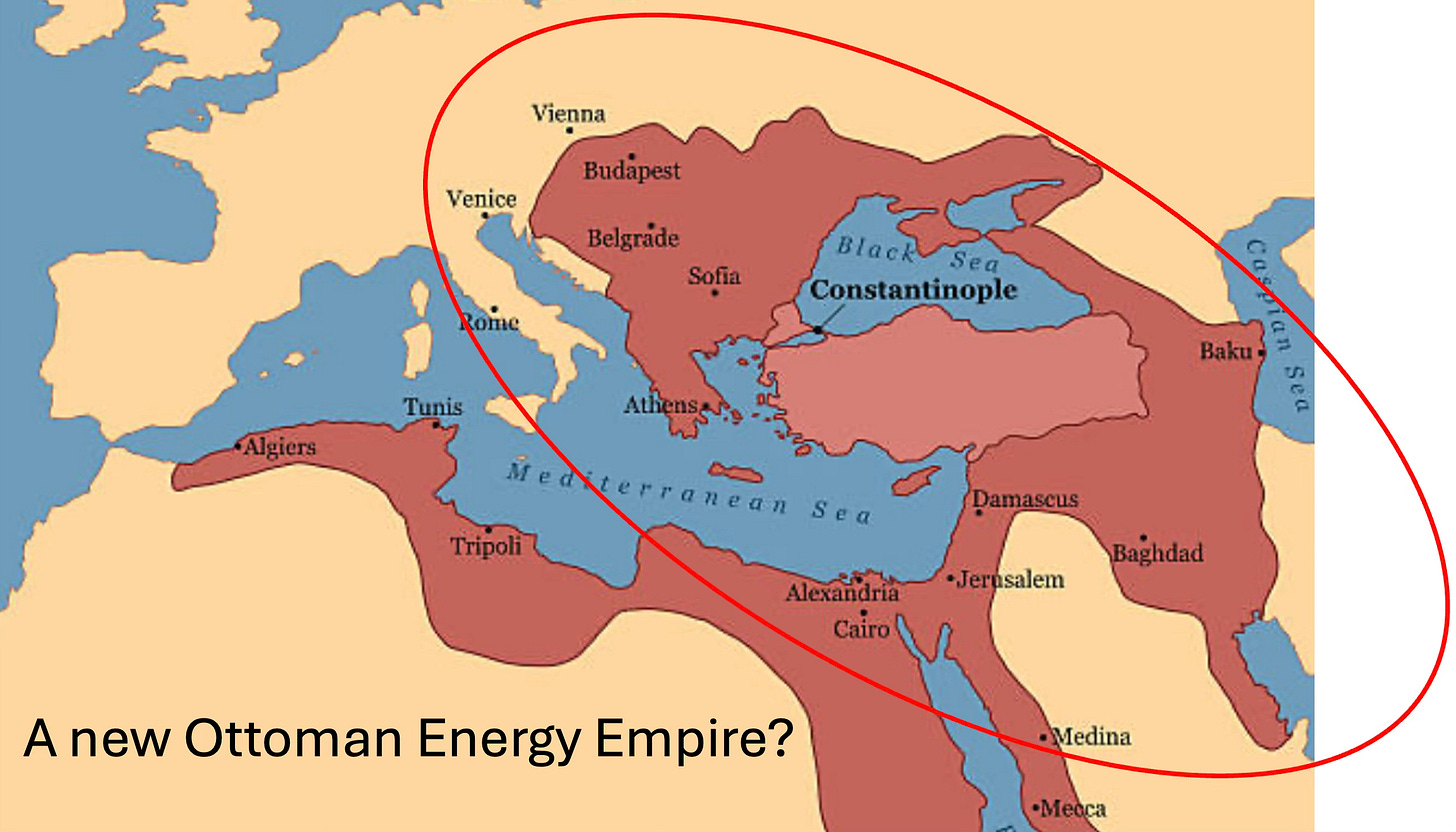

For Turkey, the stakes are even higher. The notoriously power-hungry president of the country, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, is in a position to recreate the Ottoman Empire, if not politically then economically: sourcing oil and gas across the Middle East and distributing it to southeastern Europe and up until Hungary and Austria, plus Greece and Italy. Such a strategy will provide Turkey with massive political and economic influence over large parts of Europe.

(Ottoman Empire at its largest expanse in the 17th century)

In parallel, it will reduce Russia’s influence dramatically3. North Dome is only 10% depleted and could potentially serve even more countries in Europe for the long run.

The U.S. of course happily plays along as it wins on two fronts: Russia’s influence on Europe is diminished, and Qatar’s attention shifts away from Asia.

A 1,500 km pipeline is a huge and complex infrastructure project, and constructing it will take 10-15 years. But it is a geostrategic power move, and Turkey is in for the long game. North Dome is three times the size of the U.S. Marcellus field, and five times the size of Russia’s biggest gas field (which is estimated to be 90% depleted). Connecting it to Europe would dwarf NordStream in significance. Little noticed, Turkey has built itself into a key energy hub over the last years; adding North Dome would consolidate its position and establish a new global energy force.

As always, let me know what you think!

All the best,

John

Dear friends, readers,

This is the last deep dive in 2024. I just wanted to take this opportunity and thank you all for your support and encouragement! It’s been a very good year and THE ECONOLOG got stronger traction on the Substack platform. This is very important for me.

Hope to see you all again in 2025! I remain fully committed – we’re at the beginning of something great!

Wish you all a peaceful time and a wonderful transition into 2025.

John

Please note that both the total reserves in a gas field and the amounts which are actually recoverable are estimates and vary depending which source reports them. But the 20% share points to the order of magnitude of the North Dome/ South Pars field.

This is another bizarre episode of European energy politics. SouthStream was found to violate some bureaucratic regulations on European energy markets and cancelled. The pipeline would have entered European soil on Bulgaria’s Black Sea coast. Instead, TurkStream enters Europe just a few kilometers south on Turkey’s coast and connects to European pipelines from there.

There’s potentially another connection between the fall of Syria and the Ukraine war. Russia is advancing in Ukraine and has demonstrated technological superiority with the recent Oreshnik rocket strike (for further reading please check here). It seems Russia will achieve its strategic targets. You might see an element of retaliation in the sudden acceleration of events in Syria, and the fall of the Assad family, even though this is a bit of a stretch.

This is well thought out. Not an idea that I’ve seen get traction elsewhere, so kudos to you for getting it out there for consideration,. Turkey and its state pipeline company have a long history of creating transit corridors for oil and gas. Two thoughts to consider: one. A pipeline from Qatar to Turkey will be in the $5 billion range. While it could be financed directly from sovereign wealth, It’s more likely that it would be project financed and a multi stakeholder multi country coalition. Two. One of the big commercial questions in multi country gas pipelines is: where is the point of sale from producer to consumer? Producers generally prefer to sell at the outlet of the pipeline, and consumers prefer to buy at the inlet of the pipeline. Why? Pipeline tariff, and most importantly, pipeline capacity allocation is the responsibility of the entity owning the gas in transit.

Erudite and scholarly article, thank you.