Events unfold more quickly than I can write. I’ve long scheduled this piece as a follow-up to “Everything Must Go”, a first take on the decline of Germany. But one day after the U.S. elected a new government, Germany’s government collapsed which gives a whole new spin to events and required some re-writing.

The fall of the government comes at the worst moment, during the largest economic crisis in decades. Even though the country is now without leadership, chancellor Scholz didn’t call snap elections but seems to be waiting until next year – losing more precious time, letting Germany sink deeper into chaos.

Again, this is a high-concept paper. I haven’t seen my central thesis posted anywhere before – be the first to read it here! I hope it is useful and inspiring for your own thinking and discussions. Please leave a ‘like’, and if you haven’t subscribed, please sign up! It keeps this channel going.

The history of one of the world’s best known quality promises did not begin in Germany. It began in Britain. In the nineteenth century, Britain was the leading industrial power. British engineers had developed the steam engine and built huge industrial parks around it. The Royal Navy dominated the world’s seas since it broke the Spanish and French Armada at Trafalgar in 1805, enabling Britain to trade globally and export its manufactured products into every corner of the world. Its engineering know-how allowed Britain to produce them at low costs but the highest quality standards.

But other countries were catching up. It was a time when publishing copyrights didn’t exist in countries like Germany. If people found a manual useful, they didn’t hesitate to copy it, improve it, and distribute it (that’s also the origin of the phrase “a country of poets and thinkers”). In the years that Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein was the most-widely read text in England, an all-time classic in literature, in Germany the most-read text was a pamphlet on the best techniques to dye leather.

Germany’s increased budding wasn’t lost on British industrialists and politicians. They saw an increase of German imports of supposedly inferior quality and thought of ways to protect England’s consumers from wasteful expenses or even worse, physical harm (I’m being cynical. Producers were looking for protection). British manufacturers came up with a fancy tagline. In 1887, the British parliament passed a law which forced German producers to stamp it on their goods: MADE IN GERMANY. The marker was intended to communicate “cheap and bad”. Turns out, German manufacturing was actually superior, and the tagline became an immensely powerful and successful seal of quality.

England’s decline

Britain was running a global empire in the nineteenth century. Building and maintaining it was costly. Britain invested heavily in its colonies, building and expanding infrastructure like railroads, bridges, and businesses like plantations and mining operations. During that time, the country experienced a large current account surplus, again confirming the heavy net foreign investments of the empire1.

But in the late nineteenth century, another technological revolution took over: the electrification of economies. While Britain kept expanding infrastructure investments abroad, Germany and the U.S. invested heavily in the new electrical economy and the emerging chemicals industry. Both countries soon surpassed Britain’s industry as a result.

Recurring patterns

Sometime in late 2018 or 2019 I attended an investment outlook presentation of a famous west coast money manager. I don’t remember when exactly, but it took place just before the pandemic years. Their chief economist was a German, so I asked him, thinking about the British experience, isn’t it a worry for him to see the significant current account surpluses in Germany, sustained over such a long time? Stats like that are often considered a sign of strength, but in reality, they point to excessive investments abroad, potentially hollowing out the manufacturing base at home.

The economist put on a knowing, slightly condescending smile and said no, not at all, because in the end it’s still German companies, and it doesn’t matter if Volkswagen/ BMW/ Mercedes-Benz invest in Germany or in China.

Unfortunately, what’s happening now is an eerie parallel to what happened in Britain a century ago. There may be additional reasons, but the fundamental forces are the same. Investment in Germany is dropping at frightening speed. In September, semiconductor company Intel announced to delay a massive investment of €30 billions to set up a chipmaking plant at Magdeburg, a town near Berlin. Together with the plant, 3,000 jobs are in a limbo now. Intel will reallocate investments to expansion projects in Arizona, New Mexico, Oregon, and Ohio.

A study of the German IW Institute, an economic think tank, published in March2 showed that foreign investment into Germany dropped to the lowest in a decade, including from neighboring EU members. While German companies sent out about €90 billion to the Benelux countries and France in 2023, Germany received hardly any money in return.

The reasons listed most often converge on high labor costs, high energy costs, and unpredictable government funding programs. Let’s take a look in turn.

Energy prices

(Energy prices for industrial users. Source: BloombergNEW, FT)

While it’s become a cliché that German energy prices are high, it’s worth remembering how they came about. Right after Russia’s invasion of the Ukraine, the ministry of the economy asked to carry out a check on the country’s nuclear power plants. A few of them were still operating but scheduled to shut down. Would it make sense to keep them running, as the country faced a potential shortage of gas?

Two working groups looked into the issue, at both the ministry of the economy and of the environment. They concluded that keeping the nuclear plants running was technically feasible, safe, and economically preferable.

Nevertheless, Robert Habeck, Germany’s minister of the economy, decided to shut them down, publicly claiming the working groups had recommended closing them for safety reasons. It was a major scandal, however marginalized in communication by the media outlets (for more details please check Peak Panic).

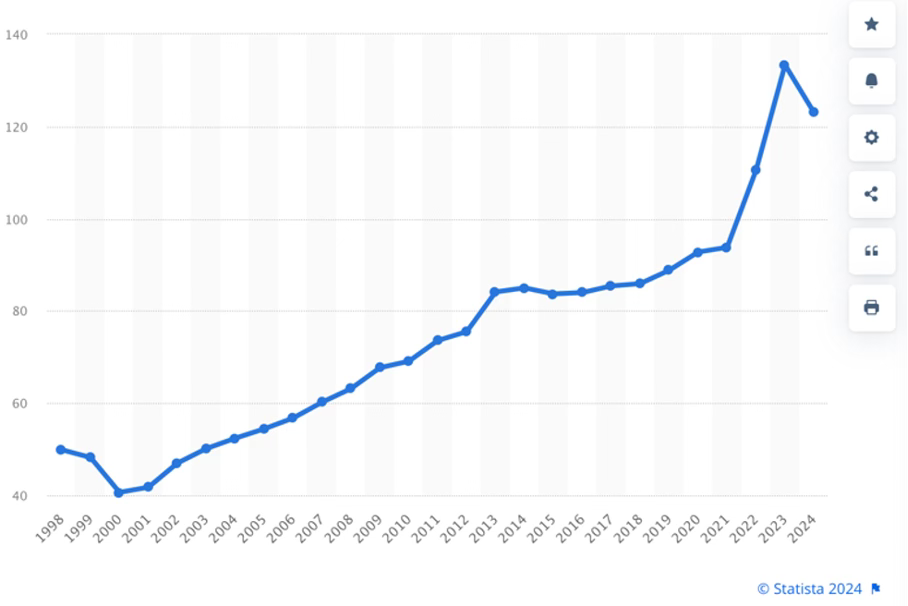

Here’s how energy bills responded:

(Average monthly energy bill of a German 3-person household. Source: Statista)

Unreliable funding programs

The German government set up a huge fund to sponsor the green transition, aptly called the “Climate and Transformation Fund”. It was supposed to provide subsidies for industrial corporations to replace coal and gas energy, for household to convert home heating to heat pumps, and for consumer to buy electric vehicles. Exactly one year ago, the fund collapsed. It turned out that a major source of financing, worth around €60 billion, constituted an illegal breach of federal deficit limits (the government intended to repurpose an unused covid relief fund). Suddenly, the government was left with a €60 billion hole in its budget and declared an emergency halt on all government spending programs.

The impact was dramatic. As subsidies for electric vehicles ran out, purchases collapsed. It turned out that without massive government incentives, there was no value proposition, and consumers didn’t want them. The Climate and Transformation Fund was also supposed to sponsor Intel’s plant at Magdeburg. No coincidence that Intel delayed (if not completely pulled) its plans to build a facility. Taiwanese competitor TSMC intended to set up a plant as well, again on the support of subsidies of the German government. They will most likely be the next to cancel plans.

The Intel decision isn’t just a painful confirmation of a negative trend for Germany, it’s even worse. In September 2023, the EU passed its CHIPS act to improve EU chipmaking capabilities. The act was modeled (and named) after the U.S. CHIPS act and was supposed to attract global manufacturers to Europe with the help of lavish subsidies. The act targeted to double the EU’s output of microchips to 20% of global production. Intel was promised almost €10 billion for the plant. The delay (if not cancellation), coupled with continually worsening conditions in Europe, has crashed this key European strategy.

Central planning, one of the great success stories in economic history

Most observers still don’t realize the full extent of Germany’s energy transition. Government planners have drawn a completely new energy grid on the whiteboard: solar, wind, hydrogen. A great, central, multi-year plan to fully replace nuclear energy and fossil fuels with renewables across the whole economy – central planning, rings any bells? An economic system which has been proven to fail again and again?

(Hydrogen grid in Germany, dreamt up by policymakers, and looking good on the whiteboard. The grid supposedly is embedded, according to government documents, in the European hydrogen grid, and made up of repurposed gas pipeline. Never mind that “the European hydrogen grid” does not exist, and repurposing gas pipelines is even more expensive than building them from scratch, due to very different chemical properties of hydrogen)

Energy analyst Vaclav Smil has pointed out that in past episodes of energy transitions, it took three generations of people for a new energy carrier to take over broadly in an economy: from wood to coal, from coal to gas, etc. That’s the time it takes a society and an economy to adjust to new carriers: get to know the use cases, supply, distribution, operation, disposal, and risks in each process step, all of that taking place in a competitive market economy in which best practices prevail, leading to the most efficient outcomes and least costs.

The German government runs its transition outside competitive market forces in an attempt to speed up the transition. But at every instance, it shows that this approach does not work. Products (EVs) are not competitive without massive government subsidies, and companies don’t invest (global leaders like Intel, TSMC, and essentially all domestic industrials).

Germany’s broken investment cycle

Because of its external focus, especially with huge investments in China, domestic infrastructure was left behind long ago. The German railroad is ridiculed for increasing service breakdowns and worsening delays after decades of underinvestment; in many parts of the country, there’s still no reliable wireless communication network; many cities are far behind in fast internet connections; large parts of the population have been groomed to be hostile to technological innovation, impeding the roll out of next generation grids like 5G communications.

With its energy transition, the government has now broken the investment cycle of global companies in Germany. As the full scale of Germany’s ambition is sinking in to them, they stop putting money on Germany, as the IW Institute report and daily newscasts show. It’s almost like the government unleashed a giant steamroller which flattens the economy. Sure, with united forces you can stop it, but who wants to be the first to step in its way? Not a winning proposition.

However the ideologues in the government aren’t even worried. Their attitude is, if times are hard, so be it. Tighten your belts and stick it out.

Problem is, this works only in their imaginary fairytale world. In the real world, if German companies show weakness, they will be taken over by global competitors – and those are not going to play by German rules, but by their own rules. They will take technology home and produce where costs are lowest, but definitely not in Germany. Managed decline doesn’t exist. You move forward, or you crash hard.

Germany is not going through a consumption recession. Consumption recessions are cyclical and don’t last longer than a few quarters. Germany is going through a self-inflicted investment recession, and those are secular. Once confidence is broken, it will take years to rebuild it.

The longer Germany hesitates to course-correct, the more momentum the investment recession will gain. But again, chancellor Scholz remained undazzled. While his government broke down on Wednesday, he delayed a referendum on snap elections, actually increasing uncertainty at the worst time possible in an unbelievable display of irresponsibility.

The U.S. reached a turning point this week – Germany a new low point. The gap in opportunity has never been larger as far back as I remember.

Let me know what you think,

All the best,

John

In national income accounting, net foreign investment equals net exports.

IW Institute, March 14, 2024: “Deindustrialization: Current trends in direct investments”

I know you wrote about the "Nuclear shutdown" beforehand, but it bears repeating that this one was also a mal-advised misadventure by Merkel - a supposed "physicist" who was initially in her terms as "Minister of Environment" under Helmut Kohl a stark supporter, even a builder of Nuclear under Kohl.

Yes, that was a long time ago, in the 1990s and into the early 2000s. She then took Schröder down on the peak of his arrogance and usurped and twisted what was once a conservative-led party into a green-ish nightmare that you are seeing today with no discernible talents to be seen anywhere nor any firm and solid positions you could discern from most of the other partys - current Germany feels like it's run a uniparty circus and no one can find the exit of the tent.

Kohl himself even weighed in on Merkels solitary (!) decision to reverse positions on nuclear energy and plants, here, in 2011:

https://www.spiegel.de/international/germany/nuclear-moratorium-overly-hasty-helmut-kohl-weighs-in-on-reactor-debate-a-753125.html

I am so mad about this, I might actually turn this into a longer piece, as it bears chronicling this stupidity of a whole nation granting one individual the right to tear it down from "Energy secure" to "energy poor and insecure" in the matter of a decade.

And of course when later on, you get your North Stream 2 blown up by some drunk "yacht renters" who surely didn't have any help from anyone, they just misplaced some explosives in the deep sea after a bender, it's a one-two punch.

"Most idiotic energy politics" globally, indeed.

This is an excellent write up of what’s happening in eurrope. I personally am aware of my friends not being able to build factories in Germany, or otherwise shutting them down in pretty vital industries. Hugely depressing and seemingly a downstream effect of adopting ultra progressive attitudes towards future development without considering consequences.

When I read the hydrogen part I just thought damn. Lmao good luck Germany, enjoy your indoor snowpants