Global trade policies and tariffs are a complex, multi-faceted topic. In the posting below I provided some thoughts to start a conversation – Feel free to add your views in the comments section!

If the posting is helpful or at least entertaining, please drop me a ‘like’!

As the U.S. elections draw closer quickly, emotions are heating up on every front of society – not only in the U.S., but all over the world. Both candidates have presented economic and social programs which will have direct impacts on many other countries. In particular, Donald Trump’s thoughts on tariffs and trade policy have foreign politicians and companies worried. The EU even set up a dedicated task force to react quickly.

Both of the recent administrations, under presidents Trump and Biden, imposed tariffs against other countries, including Europe and China. But Donald Trump’s plans in a potential second term go way beyond that. Trump said he might put a blanket tariff of 10% up to 20% on all imports into the U.S. Potentially a 60% tariff on all Chinese goods. Maybe 100% on Chinese cars produced in Mexico. Those plans are a huge departure from current economic policies, and they are going to reverberate around the world.

Can he even go ahead? Does it make sense? As policymakers in other countries fall into panic mode, let’s take a step back and check the three main use cases which Trump mentioned – protect local production, replace income taxes in the federal budget, and close the trade gap with other countries.

The murky world of tariffs, subsidies, and other distortions of free trade

Economists in general hate tariffs on imports and subsidies on exports (which, unexpectedly, have exactly the same outcome!). Import tariffs not only raise prices for consumers but lead to all kinds of distortions in the economy. Countries usually specialize in the production of goods in which they have a competitive advantage. They may have a cost advantage (the classical Adam-Smith explanation), different technologies (like the car companies in Japan and Germany), or different resources (like huge numbers of cheap workers, formerly, in China, or cheap electricity in the U.S.). And they import what they aren’t that good at producing themselves. Everybody wins. But when tariffs raise prices for import goods, the economy reallocates resources, encouraged by high prices. It takes workers and capital away from areas of strength and puts them to work in areas of weakness – not exactly a convincing strategy.

Or, maybe, are there some meaningful use cases?

Objection 1: Tariffs are sometimes needed to protect against unfair competition

Initially, Trump’s main concern was unfair foreign competition which supposedly hollowed out the U.S. manufacturing base – EU countries and China sending subsidized products into the country and destroyed workplaces. That’s why he imposed tariffs on European steel and aluminum in 2018. But was the U.S. economy really suffering during that time? Remember, economic agents (corporations, workers, investors, consumers) respond to incentives – they will always build and buy where they see the greatest opportunity. Unemployment has been exceptionally low in the last ten years. It does not appear that “unfair” foreign competition took away American workplaces. If anything, the U.S. economy has demonstrated again and again how flexible it is in adjusting to changing patterns in economic opportunity.

Here's an example. Much like China is perceived as the greatest threat to U.S. hegemony today, Japan was the biggest threat on the horizon in the late 1980s/ early 1990s. Japan was the first economy to roll out innovative manufacturing processes like six-sigma production and just-in-time deliveries1. Japan was the global leader in consumer electronics like video gaming. It was the time when books like Michael Crichton’s “Rising Sun” (1992) were published, an influential and very successful novel/ thriller which captured American angst of Japan’s rise to dominance, pushing the U.S. aside.

But none of that materialized. It was America which fully captured the potential of the electronic age. Silicon Valley mobilized financial resources and brainpower across the U.S. in another adjustment of the American economy, facing a changing environment. Around the same time that Michael Crichton’s book was published and became a bestseller, a California startup was launched which specifically addressed a key weakness in Japan’s coveted computer gaming architectures, known as Nvidia (1993) – you may have heard of it.

This is just one example how openness and adaptiveness have served the U.S. economy much better than instinctive impulses like protectionism.

Income generation?

In recent weeks, the discussion about trade policy has taken a new turn. Can tariffs on imports replace income taxes?

A long time ago, they actually did. Tariffs used to be the most important source for government revenues in the 19th century, making up more than 50% of the federal budget. In 1890, the McKinley Act raised tariff rates to an average of 50% on a range of goods. Government budgets were balanced during that time, as the prevailing thinking was to avoid deficit spending. Government spending as a percentage of GDP was much smaller than today.

General income taxes were introduced in 1913 to fund increasing expenses for social programs and government interventions in the economy. Income taxes today make up 50% of the total government budget (planned revenues of $2,447 billion in a budget of $4,890 billion in 2024), pretty much the same relative contribution as tariffs in the 19th century. Can the U.S. revert to 19th century finances?

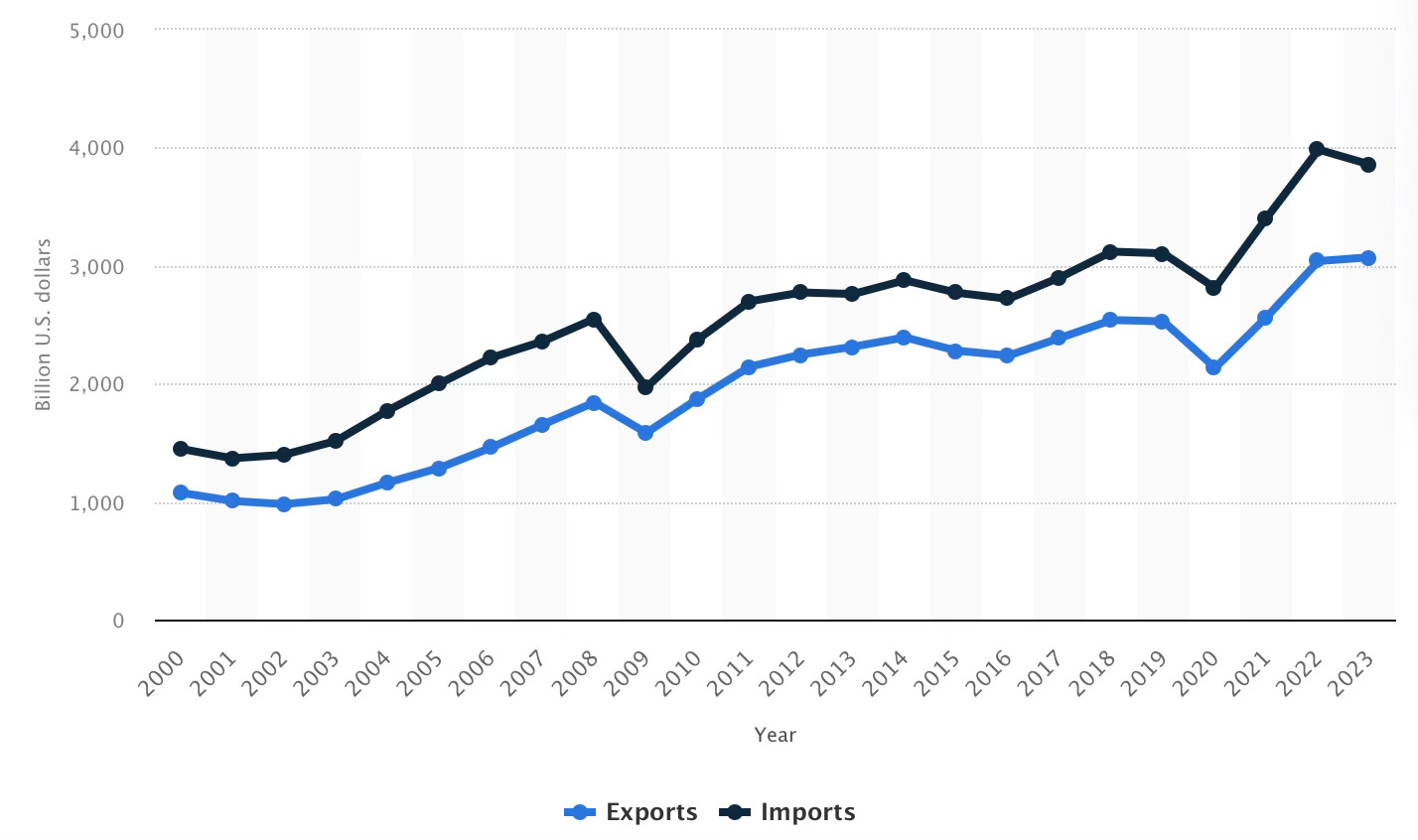

(U.S. exports and imports. Source: Statista)

Let’s do the math. The World Bank estimates that the average tariff across all U.S. imports, weighted by trade volumes, is 1.5%. The World Trade Organization (WTO) estimates it at 3.5% (simple average, on most-favored-nation/ MFN basis).

If Trump raises tariffs to 10%, the policy will create additional revenues for the government of about $300 billion on total expenditures for imports of around $3.8 trillion (or almost exactly one-eighth of income tax revenues).

The big question now is – will product volumes decrease, because the foreign sellers receive only $3.4 trillion?

It is well known that Trump drives a hard bargain and typically tries to roll off the costs of his policies to foreign countries (just consider the border wall with Mexico). It’s pretty obvious to me that Trump thinks he can strong-arm foreign countries into price cuts to maintain their market share – essentially forcing them to absorb at least some part of price increases of tariffs.

Close the trade gap? Why?

The U.S. trade deficit with the rest of the world is large and has been growing. However:

trade deficits are a direct result of the dollar’s role as the global leading reserve currency

and they are actually a huge benefit for the U.S.

Consider what most people do when they buy a home. They can’t finance the house from their current income, so they take out a mortgage from a bank. The home loan allows them to spend more than they earn.

An economy, taken as a whole, isn’t much different. It produces a number of goods and services (generating income in an economy), and it consumes a certain amount of goods and services. If the economy consumes more than it produces, it imports the balance. If it produces more than it consumes, it exports the balance. The size of the trade balance, in the end, is determined by consumption patterns: on aggregate, do people in an economy spend more or less than they produce.

For most countries, excess spending will over time lead to currency depreciation, in turn leading to a rebalancing of the trade balance. This was exactly the reason why the Bretton-Woods system broke down in the end.

But the dollar is the anchor of the global monetary system. Essentially all critical resources are essentially all traded in dollars. Countries around the world therefore need to build dollar reserves for trade in those commodities. Their central banks buy up the dollars which American consumers, including the U.S. government, spend overseas.

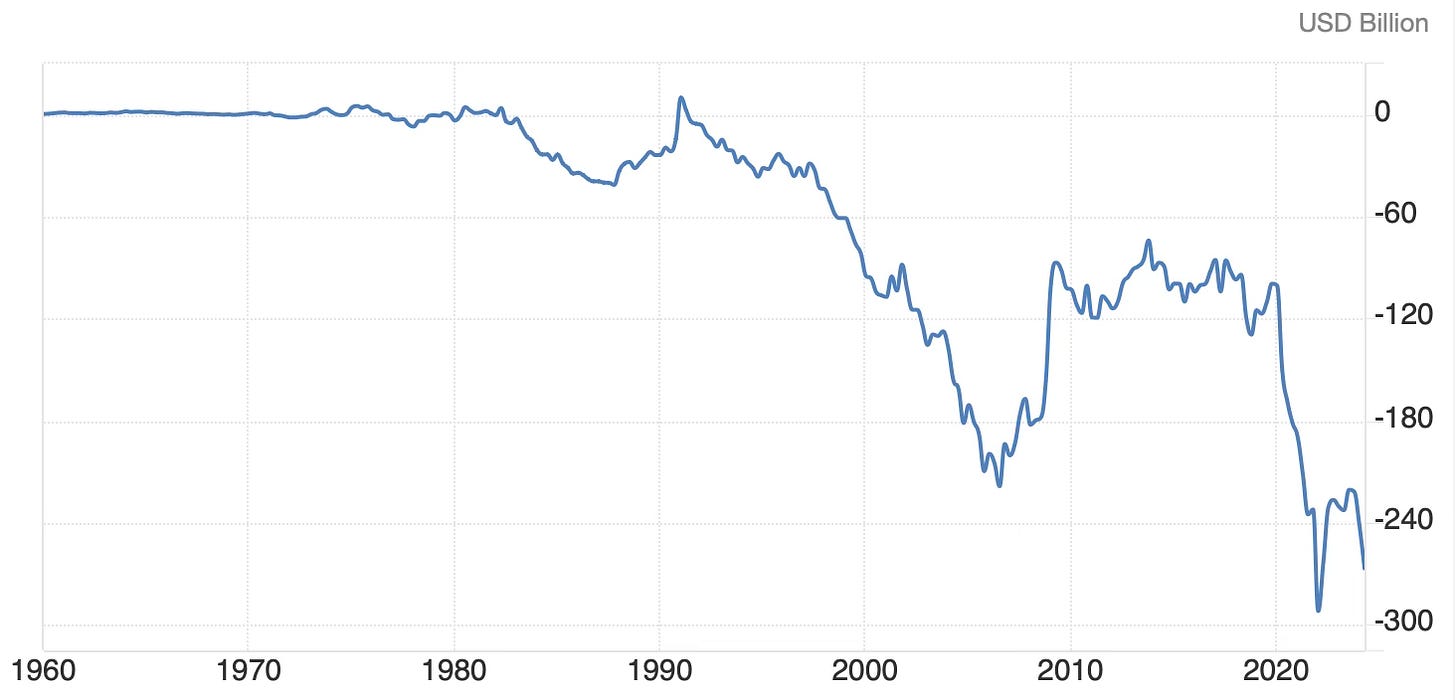

Therefore, soon after the dollar took over the economic role as the world’s leading reserve currency after the Bretton-Woods system broke down in 1973, U.S. trade imbalances started rising.

(U.S. current account balance. The current account includes the trade balance (the largest component by far), net investment income from foreign investment assets, and money sent/ received by foreign workers)

It’s a built-in feature of reserve currency status, and it is a huge benefit for the U.S. as it supports excess consumption without putting pressure on the currency exchange rate.

Europe’s Rapid Reaction Force

European politicians are panicking. The EU Commission has set up a Rapid Reaction Force to respond quickly should Donald Trump go ahead with his plans. “We will hit back fast, and we will hit back hard,” a European diplomat said. Another one: “Brussels has a list that is ready, and they are pretty confident they can win this trade war”.2

It seems the European strategy response is maximum escalation: inflict as much pain as possible, staring down a shocked-and-awed opponent. Problem with that is, to be credible, you have to act from a position of strength. I, personally, will never be able to stare down Connor McGregor, no matter what tantrum I throw.

Europe is in a much weaker starting position than the U.S. in all three key dimensions of any coming conflict.

It is much more vulnerable. Any trade disruption will hurt Europe much more than the U.S

(Source: Our World in Data; Trade as a share of GDP)

European countries are much more dependent on trade. The three largest economies Germany, France, and Italy have trade shares above 70%, compared to a world average of 63% and a U.S. exposure of 27%. Even if much of that is intra-EU trade, the U.S. is Germany’s most important trading partner, in particular since Germany shifted much of its trade from China to the U.S.

European economies are much weaker. Germany is going through the longest recession since 2000, and inflation is rising. The EU is a whole is barely breaking even, and a larger trade disruption will push other countries over the edge as well.

The EU has much lower bargaining power. The U.S. has a strong federal government, but the EU commission has to go through complicated alignment processes and has no formal decision power for its member states – each member state runs central decisions through its national parliaments for ratification.

Germany is fully absorbed in its weird energy transition which is creaking in every corner, and it will have little time and attention span for a major economic confrontation with the U.S.

And of course, the U.S. still has a huge bargaining chip in its hands – it still provides most of NATO’s military cover for the EU and drives the defense of Ukraine.

Turns out, Europe has a rather weak starting position in any “trade war”.

Trump is known to challenge conventional wisdom, and why not give it an unconventional thought how to improve finances of the average citizen? But tariffs lead to an enormous chain reaction of unintended consequences. The U.S. economy is basically at full employment, so there’s no need for protection. The economy should allocate limited resources to where they have the biggest impact. Use electrical energy to develop AI models, not to melt more aluminum.

A controversial topic – happy to hear your thoughts!

All the best,

John

Ironically, many of those ideas were developed by an Austrian-American management consultant, Peter Drucker.

POLITICO Oct. 21, 2024

It was Econ 101 that tariffs are bad.

Smoot/Hawley anyone?

How the hare brained scheme of tariffs being some kind of economic panacea is beyond comprehension. Certainly fails any type of analysis.

Neither Harris or Trump have proposed pro-growth economic policies. Instead, they have chosen to pander to select groups in search of votes.

The key different here is that Kamala’s bad tax proposals would need approval of Congress, but Trump’s tariffs are within the President’s purview.

In other words, Trump can unilaterally force bad policy onto Americans with nothing to counterbalance him.