The Yield Curve Conundrum

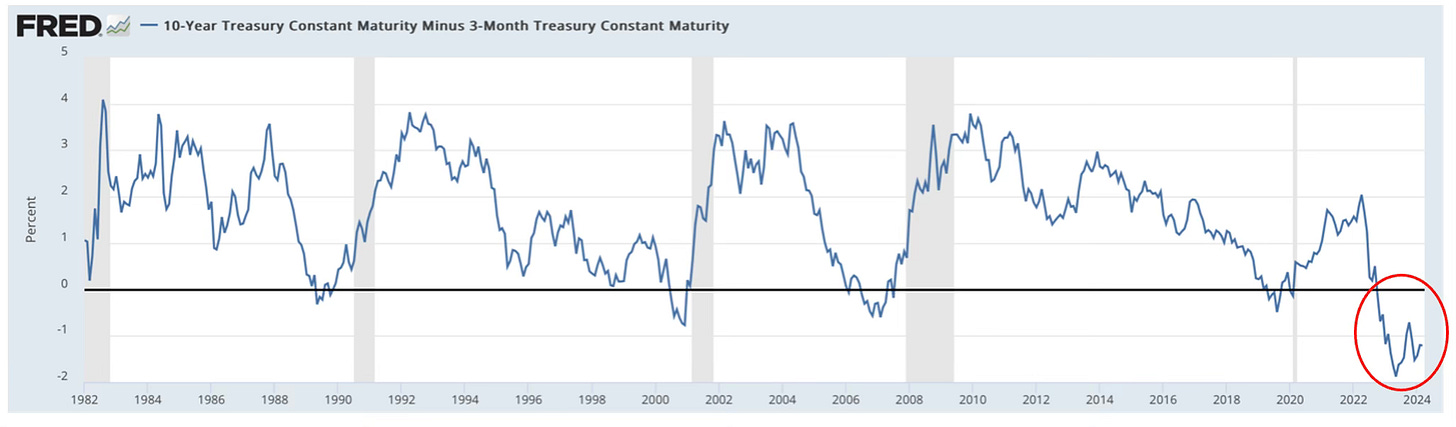

There is a major riddle in financial markets today. Long-term interest rates are below short-term interest rates, a phenomenon called an “inversion” of the interest rate term structure. This means that the yield on a short-term bill is higher than that of a long-term bond. Most of the time, it is the other way round: the longer the term to maturity, the higher the yield of a bond.

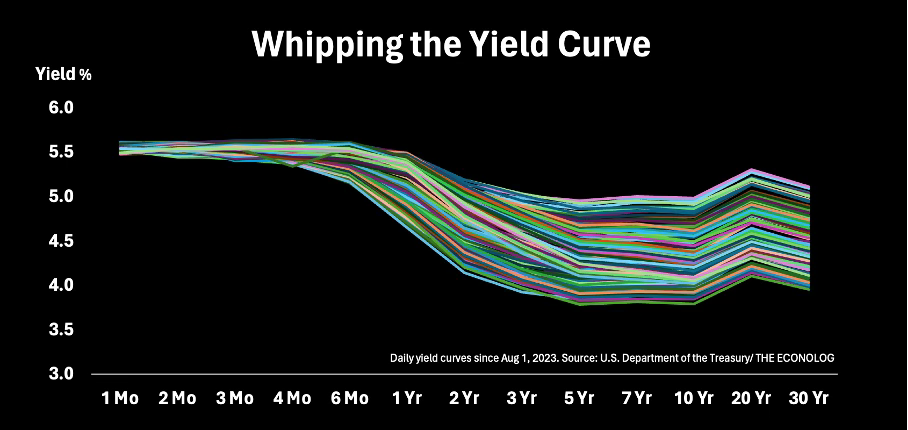

What is puzzling today isn’t only the size of the inversion (the largest in modern times), but also its persistency (the longest ever).

(Yield curve inversion: ten-year treasuries minus 3-month bills1)

This is not a trivial observation, or of purely academic interest. The inversion is a big problem for banks, whose expenses are tied to the short end of the yield curve (deposits) but which earn at the long end of the yield curve (loans, mortgages), and for other financial institutions which make their money from the yield curve. It is a problem for the valuation of financial instruments which often employs the yield curve. And it is going to be a huge problem for the U.S. Treasury Department when it tries to raise money for record government expenditures.

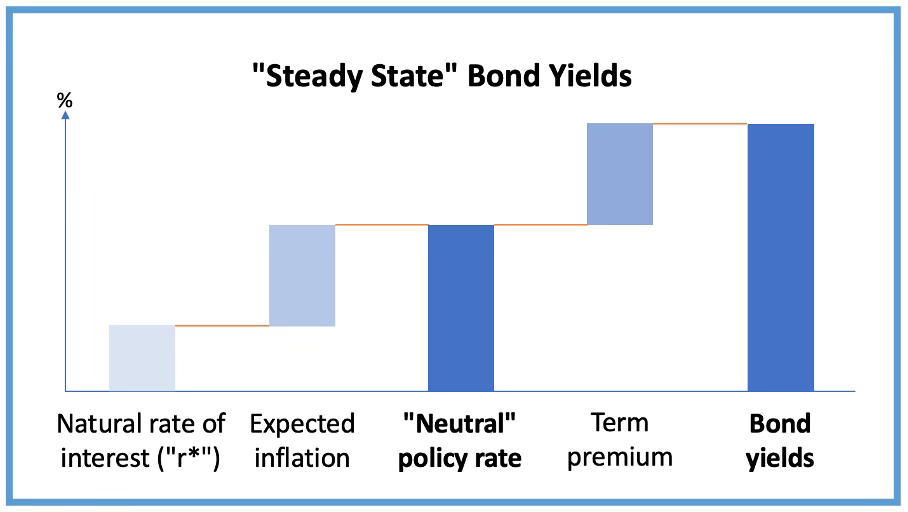

The normal shape of a yield curve is upward sloping. “Normal” means, what has been observed most of the time in financial markets, and what makes sense from a theoretical point of view. The longer you hold a bond, the larger the investment risks are, and investors demand higher risk premiums to hold the bond. Over the last forty years, the term premium for ten-year bonds has been 1.5% on average, but sometimes as high as 4%. It was almost never below 0%. But one year ago, it fell to -2% and never really recovered. Something seems broken in the gearbox of financial markets. Time to take a closer look.

Every good story needs a villain

Ben Bernanke, a Princeton University economist, was appointed the 14th chairman of the Federal Reserve in 2006. He took over from Alan Greenspan and served until 2014. Bernanke was known by an unfavorable nickname, “helicopter Ben”, which he acquired after a speech in 2002 in which he said deflation wasn’t ever going to be a problem. He would simply rain money into the economy from a helicopter, proverbially speaking.

An opportunity for Bernanke to test his approach opened much sooner than he expected. The Global Financial Crisis arrived in 2008, two years after he took office, and Bernanke lived up to his name. He showered the economy with an unprecedented flood of money in what soon became known as Quantitative Easing (“QE”). Much has been written about it, and the size of the operations and many of its consequences are well known today. But one central aspect has been largely overlooked. With QE, Bernanke changed the way how central banking works fundamentally. Let’s take a quick look at the basics. No formulas, just the intuition.

From scarce reserves …

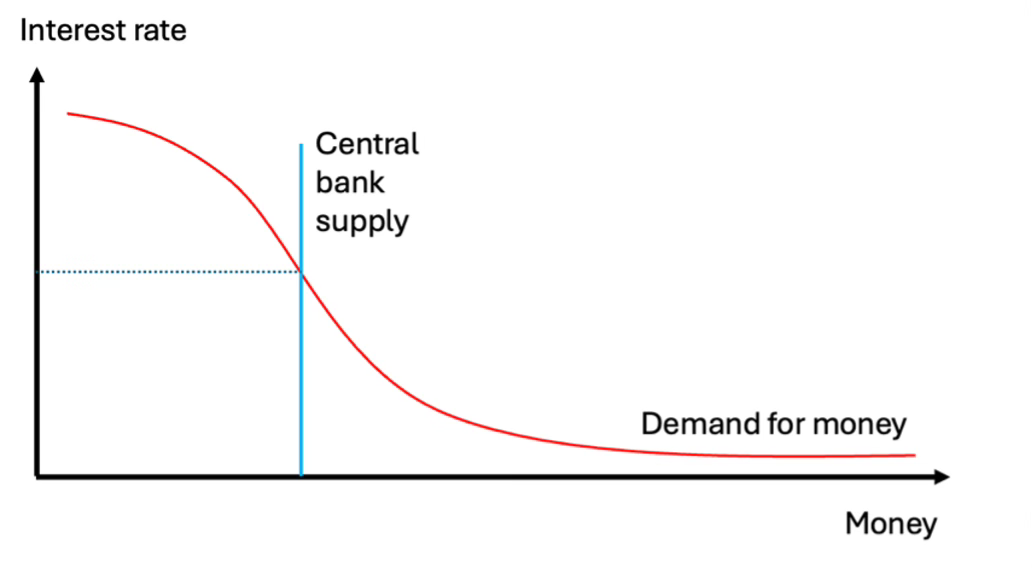

Central banks have essentially one job only: supply the economy with money. Central banks do this by buying (and occasionally selling) assets such as bonds, or in older times gold. As the central bank pays with central bank currency, it increases the supply of money. The more money is around, the lower interest rates are, and vice versa.

With its daily security purchases and sells, the Federal Reserve targeted the level of the federal funds rate, an interbank interest rate on funds which banks borrow to fill any gaps in their minimum reserve holdings2.

… to ample reserves

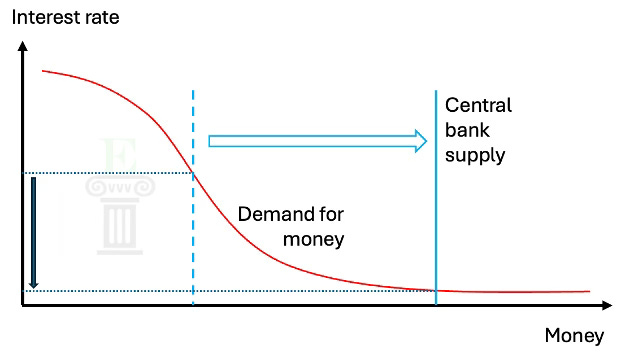

But that mechanism was unhinged due to quantitative easing. The Federal Reserve added so much liquidity to markets that short-term interest rates fell to essentially zero.

In consequence, the daily operations of the open markets desk to steer interest rates were rendered ineffective. Taking out or adding a few billion dollars didn’t have any impact on policy rates, because markets were wading in trillions of dollars of excess liquidity after years of QE. In the chart above, consider what happens when you shift the blue line left or right a bit: because the red line is more or less flat, the intersection of the curves won’t move up or down. The Federal Reserve called it the “ample-reserves regime”.

How do central banks stay in control of policy rates in such an environment?

The Federal Reserve introduced, in deus-ex-machina-style, two new policies: It started paying interest on reserve deposits, called Interest on Reserve Balances (IORB), set just above the fed funds rate. For institutions which didn’t have access to accounts at the Fed, e.g. money market funds, it launched the Reverse Repo program3. The interest rate on reverse repos was set just below the fed funds rate.

Those two rates became the new anchors for the financial system: whatever a bank wanted to invest in, it had to earn at least as much as the IORB, because otherwise the bank would just leave the money at the Fed.

This is a new paradigm which still hasn’t been broadly understood by many practitioners. The Federal Reserve (and other central banks like the ECB which follow the ample-reserves approach) doesn’t manage the key policy rates via open markets operations any longer, but directly determines the upper (IORB) and lower bounds (RRP). It can raise and cut them without buying and selling bonds.

Ah … wait a moment … what was I going to write about today? Yeah, right, yield curves!

In the scare-reserves regime (pre-2008), policy interest rates were equilibrium, market-clearing rates which balanced the supply and demand for money. Bond market yields built on the fed funds rate with term premiums, and together they formed the yield curve.

But in the ample-reserves regime, that link is broken. The formation of bond yields takes place separately from the fed funds rate, because it isn’t a market-clearing price any longer. Bond markets form their own expectations of real interest rates and inflation, and bond yields therefore move largely independent of the “administered” short-term rates, as the Fed now calls them.

Before 2022, that distinction was little more than semantics. Interest rates and inflation were so low that the lower boundary, the RRP rate, wasn’t even needed as a constraint.

But when the Federal Reserve raised policy rates from early 2022 until summer 2023, the disruption quickly became apparent. The federal funds rate was raised to effectively 5.33%, but bond yields stubbornly stayed below.

Does it matter? And what’s the outlook?

Under an ample-reserves regime, there’s no reason to expect that the yield curve unwinds its inversion. The structural drivers simply aren’t there any longer to the same extent. This is a big problem for banks, whose sole economic reason to exist is to transform short-term deposits into long-term loans and live on the term structure of interest rates. If the term structure breaks down, the basis for that business model is gone.

It also matters for the current guessing game about when the FOMC will cut policy rates, and by how much. The hope of market participants is that a cycle of rate cuts, initiated in 2024 but going much longer, will ultimately filter through to bonds yields and lower them. All assets whose valuations are based on bond yields will benefit in such a scenario. In particular, the expectation is it will decrease the valuation gap of equities compared to bonds. I don’t think this is going to happen. The valuation gaps to equity markets will probably remain in place or become even worse.

Will the ample-reserves regime stay in place?

Since the summer of 2022, the Federal Reserve has been unwinding its bond portfolio, and has largely absorbed excess liquidity which had been parked in the RRP (remember the RRP is the lower backstop for the fed funds rate).

If the Fed continues QT, it will start eating into bank reserves, and that’s going to be much trickier. Bank reserves are stickier than tier-1 liquidity for a number of reasons: Banks need reserves as part of regulatory requirements (liquidity coverage ratio limits). Banks started building reserves in 2023 to prepare for a potential recession and are now adding to reserves in anticipation of a crisis in commercial real estate. They don’t want to be caught on the wrong leg like in 2008, when liquidity disappeared in the mortgage crisis.

In recognition of this adjustment, Fed chairman Jay Powell acknowledged after the FOMC meeting last Wednesday, March 20, that “the general sense of the Committee is that it will be appropriate to slow the pace of runoff fairly soon”. Powell however also confirmed to keep the ample-reserves regime in place.

Why was the ample-reserves regime even launched?

Ben Bernanke launched the ample-reserves approach after the GFC to push down long-term interest rates, which was supposed to stoke animal spirits and investments in the real economy, and to reinvigorate growth.

But the initiative had pretty substantial, unintended consequences.

Money supposedly created for the economy found a new home mostly in money market funds and on bank balance sheets, from where it was quickly returned to reserve accounts at the Fed4.

As benchmark yields declined, the prices of assets which are sensitive to interest rates shot up across the board: bonds, equities, and real estate performed extremely well for those who owned them, but made them prohibitively expensive for those who didn’t. As a result, home ownership has become unaffordable for large parts of the population in the U.S. and in Europe, whose ECB uses the same approach.

Excess liquidity laid the ground for the huge boost in inflation which was eventually triggered by supply chain bottlenecks after the pandemic and the energy price shock after Russia’s invasion of the Ukraine.

Quantitative easing was without a doubt the biggest experiment ever in central banking, and probably the least thought-through one. Unfortunately, as market participants have locked it in, there’s no realistic way to terminate the program.

Again, this may be a controversial viewpoint regarding the outcome, but in my discussions in recent weeks it was obvious that many market participants have not caught on to this new paradigm for central banking. As always, happy to hear your thoughts on this.

Best,

John

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, 10-Year Treasury Constant Maturity Minus 3-Month Treasury Constant Maturity [T10Y3M], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

Commercial banks have to keep a certain fraction of their deposits at the Federal Reserve. Before 2008, they didn’t receive interest on those funds which obviously the banks didn’t like a lot, so they kept their reserves at the bare minimum. When they fell short, banks borrowed funds from other banks to fill the gap.

In a reverse repo (“repurchase operation”), the Federal Reserve sells bonds from its large portfolio to investors like money market funds and at the same time commits to buying it back on day later, at a slightly higher price. The difference between sell and buy prices translates into an interest rate, the repo rate. From the viewpoint of the Fed (sell first, buy back later) this is called a reverse repo. From the viewpoint of the investors (buy first, sell back later) it is a repo.

The Federal Reserve most likely never expected how much the ample-reserves regime was going to hurt. On average, it earns investment income of about 1.5% on its bond portfolio, but it pays more than 5% on reserve balances of banks. The negative carry is at least 3.5%, or $35 billion for every $1 trillion in bank reserves. Banks currently have $3.5 trillion of reserves. Go figure. And guess who’s picking up the tab.

Many thanks John for writing this “ample reserves” regime and why the bond yield has been staying inverted and not signalling recession. A lot of commentators still look at yield curve signalling in the traditional way but indeed QE has changed bond yield signalling.I have great admiration for people working with/in the bond markets as they appreciate macro much more deeply!

Many thanks for the restack!