Dear readers,

this is the next piece in the energy series which I mentioned recently. Again, it was quite research-intensive, and I think it offers some perspectives which you probably haven’t heard anywhere else. To keep this newsletter going, may I please ask you to subscribe if you haven’t done so? It’s free for you, but makes a big difference for me.

On September 26, 2022, mysterious explosions destroyed natural gas pipelines Nord Stream in the Baltic Sea. Nord Stream connected the Russian city Vyborg, located near the border with Finland, and Greifswald, a German city. Nord Stream was a key component of the European energy infrastructure, and a key cash engine for Russia.

Europe was shocked stiff. The world was just emerging from more than two years of pandemic lockdowns, economic and personal restrictions, and insecurity about the covid endgame. And right now, as the recovery started and the outlook on life became brighter, a key energy source was gone?

Germany, in particular, had made gas energy the backbone of its economy. In 2011, after an earthquake and a tsunami destroyed the Fukushima nuclear power plant in Japan, Chancellor Angela Merkel announced that Germany was going to shut down the country’s remaining nuclear power plants (for a more detailed story on the German nuclear power angst please check here). Merkel thought it was an easy decision, because Germany and Russia were just completing construction on Nord Stream 1, a pair of pipelines which connected Germany directly with Russia’s enormous energy reservoirs. Gas quickly became the most important energy source for households (more than 40% of total energy) and industrials (>30%). Russia supplied 50% of Germany’s demand.

As Russia turned increasingly hostile towards neighboring country Ukraine from summer 2021 and in February 2022 invaded the Ukraine, European gas prices shot up from below €30 per MWh to almost €200/ MWh. But when Nord Stream blew up, Germany was suddenly facing a scenario in which there would be no gas deliveries at all, irrespective of its price. And winter was coming. A new threat, potentially more lethal than Covid.

But that scenario never played out. Gas inventories never reached critical levels. Somehow, gas still arrived on the continent in sufficient quantities. And despite all the economic sanctions, Russia’s war chest was growing. Time to take a closer look.

Unintended consequences

The EU has two large suppliers right at its doorstep: Norway, which sits on huge oil and gas reservoirs in the North Atlantic and which operates the world’s largest gas rig (“Troll A”), and Algeria, another country on the list of the world’s top ten gas producers.

There’s just a small problem: the easiest way and most economical way to transport gas is in pipelines. But after Nord Stream was destroyed, and Russia side-lined, the only remaining pipelines with a major supplier are with Norway. A pretty significant concentration risk, as the experience with Russia has shown.

Europe is therefore busily building and expanding a network of LNG terminals along its coasts to take delivery of liquified natural gas from Algeria, Qatar, the USA, and other countries.

There’s a key structural difference between pipelines and terminals. Pipelines are a closed loop between sender and receiver, but LNG terminals are open interfaces. Let your imagination run wild.

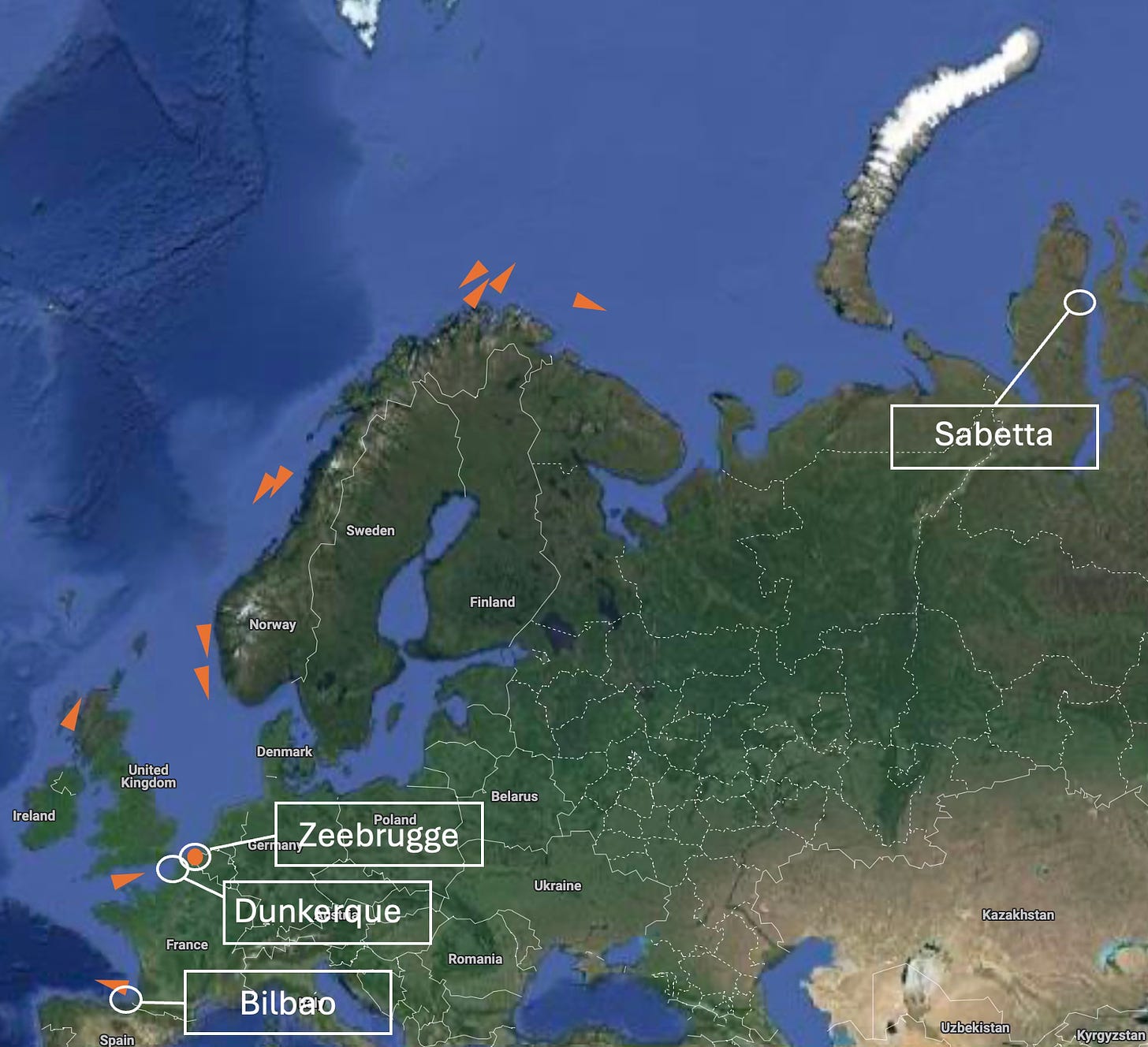

Turns out, Western Europe is not the only region which is building LNG terminals. In 2019, Russia finished construction of its Sabetta terminal on the Yamal peninsula, far north in the Siberian tundra. Sabetta is connected with Siberia’s gigantic gas fields.

(Sabetta harbor)

Yamal is a remote, inaccessible area 2,500 kilometers northeast of Moscow on the Kara Sea. In winter, the sea often freezes, and only icebreakers can make the passage to the west. Ships pass either the northern or southern tip of Novaya Zemlya island, depending on the conditions, then bear south-west towards Norway (image heading south for Norway). After travelling along Norway, across the North Atlantic Ocean, ships finally arrive at the busy harbors of western Europe.

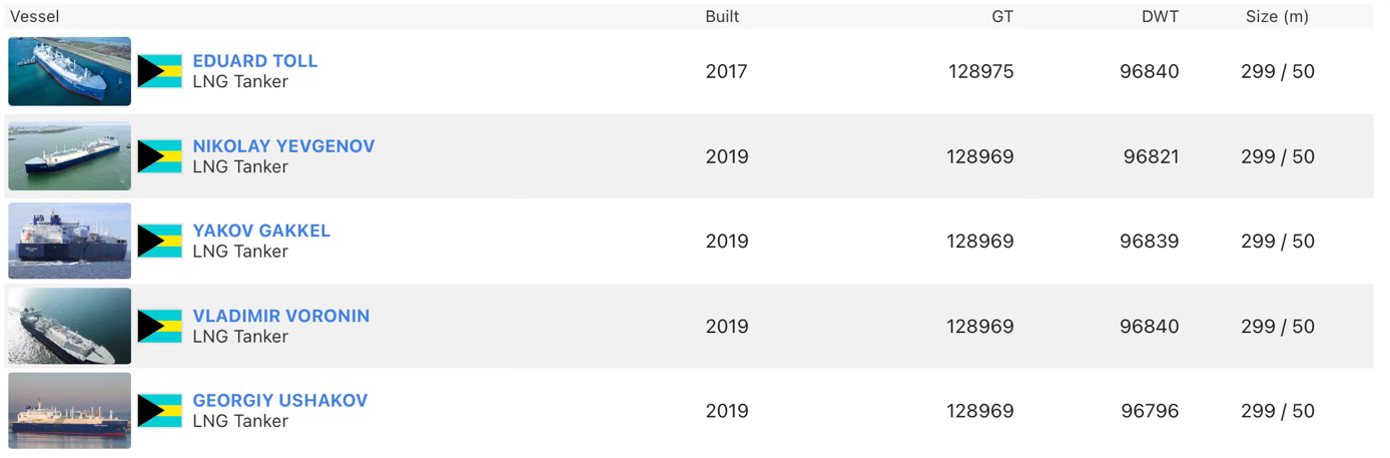

Russia has built a fleet of LNG tankers with icebreaking capabilities since 2017. They typically sail under Hong Kong or The Bahamas flags.

(Bahamas flag Russian LNG tankers)

The storage capacity of a single tanker translates into about 100 million cubic meters of gas (the density of liquified gas is much higher, and therefore volume lower than gas).1

I checked the logs on their routes, and the harbors they use. Here’s the example of the Boris Vilkitsky in recent weeks:

Zeebrugge is a harbor in Belgium, about 10 km north of Bruges (hence the name). It is one of Europe’s large LNG terminals.

I collated the positions of the Russian LNG tankers as far as I could get data (once they get into the Barents Sea, data were not available). When connecting the data on the routes and harbor logs, a clearer picture emerges.

Each arrow and the dot represent a Russian LNG vessel. There’s a handful of preferred harbors for Russian LNG: Zeebrugge in Belgium, Dunkerque in France, and Bilbao in Spain. From the travel logs it can be concluded that they have established something like a regular shuttle service between those ports and Sabetta. The travel time for a passage is 9 days. Adding one day at the port for loading and unloading, that sums up to 20 days for a roundtrip. Or in other words, 3 roundtrips in 2 months.

Now let’s do some maths.

The annual throughput of the Nord Stream pipelines was just below 60 billion cubic meters. Assuming, to make round numbers, a load of 100 million cubic meters per passage, that’s the equivalent of 600 trips, or 50 per month. For 50 trips, you need 34 ships. Russia has 15 already, which represents 45% of the Nord Stream throughput. That’s a conservative estimate, but already much more than what official statistics report.2

As Russia has gotten a taste for LNG, it is expanding production. Russia has finished development on a second terminal in the Arctic Sea, appropriately called Arctic LNG 2, situated on the Gydan peninsula just across Sabetta on the Gulf of Ob.

The missing component now is additional carriers. Russia planned to build 15 additional LNG carriers at its Bolshoi Kamen shipyard in eastern Russia. It faces two pretty significant engineering challenges: very few countries have experience in building icebreakers, and Russia isn’t one of them. South Korea seems to be one of the countries which are. Secondly, very few companies know how to build the gas containers on tankers. GTT of France is one of them.

Russia has completed at least 3 tankers with the assistance of technology partner Samsung Heavy Industries, and it’s understood that Samsung has delivered hulls for two more ships.

But both Samsung and GTT pulled out of the project after additional U.S. sanctions were imposed on Arctic LNG 2.

(Putting 1 and 1 together at the Bolshoi Kamen shipyard, east Russia)

However, the transport capacity of the 15 existing tankers is already significantly larger than what Sabetta produces so they can serve Arctic LNG 2 as well.

According to Ukrainian organization “Razom We Stand”, Russian transport companies own two additional, very large carriers, the Saam FSU and the Koryak FSU, which however cannot operate under their current ownership. The whereabouts of those ships are unknown. Presumably one of them is stationed near Murmansk, close to the Norwegian border, the other one somewhere at the Kamchatka peninsula in the east of Russia.

How have the sanctions played out so far?

Gas in some way is like cocaine. Demand is there, no matter how much you pretend it isn’t. Supply will find that demand, but the more difficult you make it for supply, the more profitable the trade will become. That’s why drug cartels are so rich and ruthless, and that’s why Russia has made so much money.

It becomes ever more obvious that not only have western sanctions against Russia failed, but they have made essentially every dimension of the Russian, and more broadly of the global energy conflicts, worse. While the latest round of sanctions may finally bite because they prevent, or at least slow down, the expansion of the LNG fleet, Russia was already one step ahead.

Sanctions on Russia increased the price of gas when Russia slowed down gas transport in retaliation, making global sales for Russia more profitable and improving Russian finances – exactly the opposite of what the sanctions intended. European gas prices are still four times as high as U.S. prices on an energy-equivalent basis.

The sanctions may have forced Russia to expand its LNG business, which on an operational level is more expensive (using icebreakers, much more expensive) than pipelines. However: Pipelines tied Russia to a specific customer. Just like Germany was largely dependent on Russian gas, Russia was dependent on German demand. LNG removed that dependency. If Europe imposes additional sanctions, directly targeting LNG, Russia can now ship gas wherever there is demand. And demand is huge. In Asia, gas could replace coal as the primary energy carrier, swapping the dirtiest hydrocarbon for the cleanest one. The geopolitical implications of any Russian expansion in the far east haven’t remotely been understood.

I know this is a very contentious topic. It just seems that current policies won’t take us anywhere close to a solution.

Let me know what you think!

Best,

John

One ton of LNG vaporizes into up to 1,380 cubic meters of gas.

Another source puts the storage capacity of those tankers at 172,600 cubic meters. That would bring the total capacity of the fleet above the Nord Stream pipeline. Now the terminals become the limiting factor – that’s why Russia is planning another 3 LNG ports.

As the famous Doomberg quote so aptly describes this situation “In the war between platitudes and physics, physics stands undefeated”.

Many thanks!!