Dear readers,

This is an ad-hoc posting in response to the dramatic events in Spain and Portugal, which just went through one of the largest electrical blackouts in European history. The investigation is still ongoing and we’ll have to wait what it brings. But the event highlights a key risk to the resilience of electrical grids which has been quietly building, and which is driven by the intermittency of renewables production.

On April 16, 2025, Spanish grid operator Red Eléctrica reported that renewable sources of energy for the first time ever fully met the country’s total demand. Over the day, wind energy chipped in 256GWh, solar 151GWh, and hydropower 129GWh, setting a global benchmark; at 11:15 a.m., solar and wind together covered just above 100% of total load.

Spain positions itself as a leader in the European Union’s green transition and has followed an ambitious plan to expand renewable sources of energy. In 2010, renewables accounted for 33% of total electricity generation; in 2020, 44%; more than 50% in 2023; and 56% by 2024. The average grid load in Spain is about 30GW over the year.

But that’s not all. Spain set up a National Integrated Energy and Climate Plan (‘PNIEC’) 2021-2030 which aims for a renewables share in electricity of 81%, and of 42% in final energy consumption (which includes energy for traffic/ transport etc., i.e. use cases outside electricity generation).

With all the effort going into generation, Spain however has neglected an ancillary component: electrical grid connections.

Germany is another of the global renewable energy champions. Already these days, in late April, German solar produces up to 46GW of electricity in the early afternoon, versus a grid load of 55 GW.

(Source: Energy Charts)

As wind and solar production have long reached critical mass, the German grid went through several near-death experience in the last few years when solar and wind generation dropped off.

On January 10, 2019, grid frequency suddenly fell from a standard value of 50Hz to 49.8Hz. It doesn´t sound like a big deal, but in a world where frequency is monitored on a mHz level (one-thousands of one hertz), this is the threshold where a system failure, a “blackout” waits.

Hertz is the heart rate of the electrical grid. Like for a human heart, large fluctuations show stress in the system. In Germany, wind generation produced 34GW of electrical power on Jan 9 but dropped quickly to 4GW on Jan 10. German grid operators prevented an additional decline of frequency only with the help of France, which switched of several industrial users of electricity.

In June 2019 grid frequency again dropped to critical levels due to underproduction. Again, Germany had to import energy from France (nuclear) to avoid a blackout.

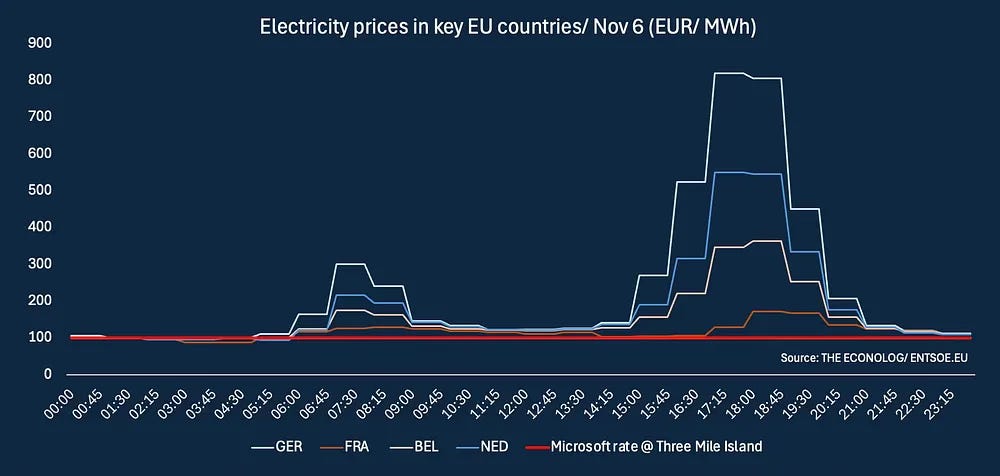

In November 2024, during dark days with no wind, Germans even coined a new term, the ‘dunkelflaute’ (‘dark lull’). Neighboring countries got pretty upset. As Germany imported large amounts of electricity, it drove up wholesale prices in the Netherlands, Denmark, and even in the southern parts of Sweden by a factor of up to 8 – from around €100/ MWh to over €800/ MWh – even if only for a few hours.

In those episodes, Germany used up all the backstops to keep its grid from failing – worrying enough, because they took place during standard operations. No large accident, no cyberattack – but the system was tested to its limits.

Spain, however, differs from Germany in a crucial feature – it doesn’t have the connectivity of Germany with other large countries, driven mainly by its geography.

Compared with Germany:

Up until 2015, the interconnection capacity of Spain was just 2% of its installed capacity, way below the EU’s target of 10% (which has been raised to 15% in the years since). In 2015, Spain and France completed construction of a high-voltage direct current (HVDC) underground cable which doubled interconnection capacity to 2,800 MW. The connection set world records for its length and efficiency. But already in 2023, the average utilization rate of Spanish interconnection was 84%. This is generally considered the upper level for industrial processes which are not exposed to unpredictable swings – but for highly volatile renewables productions this utilization rate leaves very little redundancies. Not surprisingly, almost 40% of operating hours experienced congestions in transmissions from Spain to France (and around 20% of hours France to Spain).

Because of the quick growth of renewable generation, Spain became a net exporter of electricity to France of about 2 TWh (latest reading as of 2023). This in turn made France they key shock absorber for 2 large economies: Germany and Spain. Just for comparison: France already has total capacity for imports of 12.5 GW and for exports of 17.4 GW (both in 2022), translating into an interconnection rate of 11.4%, above the EU’s target of 10%, a much more robust setup for connections but also a much more robust domestic production infrastructure.

The vulnerability of Spain is crying out loud. There is a huge mismatch between volatile production on the one hand and transmission capacity on the other hand. After years or even decades of subsidies and industrial policy, both Spain and Germany are essentially piggy backing on France to provide stability to their grids (Germany has diversified to other neighbors, including Poland, which jumps in with coal power).

Therefore, I wouldn’t be surprised if yesterday’s grid breakdown is due to operational failures at the interconnections.

Spain planned to improve transmission capacity with the Biscay Gulf project, adding 2,000 MW, by 2028, but the project is already in delay.

The EU’s ambition for renewables production so far has outrun economic considerations. Because there is still no meaningful storage at scale, excess domestic production has to be exported regardless of price, which has led to “duck curves” in prices – negative electricity prices in afternoon hours when solar production is at its peak, which are now coming even to countries like Germany.

But now the EU is also outrunning technical considerations. France has so far been able to balance European swings, acting as Europe’s battery, but even well-connected countries have gone through several near-death experiences. Spain and Portugal, much less connected, are flagging the first cracks in the system. While renewables production has been ramped up, resilience in the system – buffers, redundancies, transmission capacity – has actually decreased.

As always, happy to hear your thoughts.

All the best, and hope the lights are still on in your homes,

John

Related to that topic, I’ll add a link to another posting which addresses the dangers of large production swings - some physical processes connected to them are still little understood.

You miss the main issue: That these problems are being caused by a ridiculous policy of excessive reliance on supposedly “Green” renewables. France with its nuclear power has the only reliable energy infrastructure on the Continent!

Myth: Solar and wind are helping save our grid from extreme heat.

Truth: Preferences for Solar and Wind have made our electric grids embarrassingly vulnerable to heat waves—and cold snaps—that a fossil-fueled grid could easily manage.

https://open.substack.com/pub/alexepstein/p/myth-solar-and-wind-are-helping-save

Are there no systems engineers left? It seems that the generation builders just assume that the grid will handle whatever they build? Is it because the grid can’t attract capital? So many questions.