Everything Must Go

Germany’s sellout has begun and might strike at the country’s (and Europe’s) economic heart sooner than you think.

Germany is a world leader in many industries. As of now, the country still builds many of the best cars and is a leader in mechanical engineering. Its chemical companies are among the best in the world.

But there’s an area where Germany never really excelled in international comparisons: banking and finance. Little wonder this is where the first domino is falling. And the chain reaction might very soon hit the heart of the country’s economy very hard.

(Carola bridge in Dresden which collapsed on September 11, 2024)

When I got started in investing, Germany had five large banks with an international recognition and global footprint: Deutsche Bank was key Wall Street contender, a global behemoth which regularly appeared in top positions in league tables on M&A advisory deals, debt issuance, equity issuance, and other transactions. Dresdner Bank and Commerzbank were the go-to banks for Germany’s industrial titans to finance their global presence; and there were southern Germany’s Hypothekenbank and Vereinsbank, a real estate lender and commercial bank in Germany’s most prosperous economic region which had global ambitions as well. Those banks had grown in parallel to Germany’s industry during the time of the German Wirtschaftswunder, a period of incredibly strong growth after the Second World War. Foreign banks operating in Germany were virtually unknown those days – similarly to other European countries which had long shielded their domestic champions from foreign competition.

Europe’s Big Bang

In the late 1980s and in the 1990s, a time long before the Euro currency was created, Europe launched a process of capital markets and banking liberalization. Policymakers and financial institutions recognized that European financial services were far too fragmented and inefficient, especially in comparison to other countries and regions. They had an eye in particular on Japan, a much smaller economy than Europe as a whole, but with a banking sector which dwarfed Europe’s.

In 1986, the EU member states passed the Single European Act, with the vision of creating a unified market in which capital, goods, services, and labor could move freely. From the 1990s, financial services and banking became central to this effort. Banks could lend and borrow across borders with less regulatory friction.

The new competition quickly brought to the foreground key weaknesses in the German banking system. It had created a system of complacent banks with captive customers and static market shares, little efficiency, and little innovation. And a surprising degree of fragmentation.

In most developed economies, the top 3-5 banks usually have a market share of 60-70%. That’s a rough band, but typical. In Germany, the top 5 banks had a share of below 25%. The reason for that was that there are two more pillars in the German banking system: savings banks, and cooperative banks. The savings banks were guaranteed by the German states, and therefore had an AAA-rating. The cooperative banks were supposed to finance the businesses of their owners, usually agricultural producers. Per their statutes, they weren’t even required to turn in a profit.

Facing competition which enjoyed a huge advantage (much better refinancing terms), or weren’t even profit-oriented, the large private-sector banks soon crumbled. The two Bavarian banks merged in 1998. Fragile Dresdner Bank was acquired by Allianz Group to form something like a financial supermarket, like Citigroup at the time. It was a fashionable idea: once you’re talking about a consumer loan or savings accounts, why not throw in a life insurance contract? A financial product is a financial product, or so the thinking went. Turns out, bank employees didn’t want to be seen as insurance salespeople, and insurance agents didn’t want to waste their time selling low-fee bank accounts. The idea was rightfully deposed as one of the big blunders in abstract management theory.

But in the end, Allianz made the right move. In what must have been the greatest and luckiest sell in M&A history, the insurer sold Dresdner Bank to Commerzbank on August 31, 2008 – two weeks before Lehman Brothers collapsed, and the global banking industry went into cardiac arrest.

The combined Commerzbank/ Dresdner bank entity promptly had to be bailed out by the German government.

In August 2024, the German government decided the time had come to sell its remaining stake in Commerzbank, around 17%. The bank seemed reasonably healthy, financial markets were bullish, and the German DAX index was trading at record highs. What else could you ask for?

Money never sleeps – bureaucrats do

Well, there was a little problem. Commerzbank was trading at around 12 euros, while the government had paid 26 euros in 2008. A sale was going to realize a loss of more than half of the investment. The bank was still much weaker than before the GFC. And what the German government didn’t realize, weakness attracts predators.

The Federal Financial Agency, some sort of investment advisor to the government, asked U.S. banks J.P. Morgan and Goldman Sachs to coordinate a block sale of a 4.5% stake, kicking off on Tuesday, September 10, 2024. The government officials were a bit antsy-pantsy: would enough buyers show up for a billion-euro stake? Would the country remain stuck on the remaining 12% forever?

Telephones stayed silent most of the day. Then, shortly before midnight, a call with an Italian prefix. It was UniCredit. They wanted the whole stake.

The lead arrangers fell into hysteria. Was it even desired by Germany to have a foreign stake of that size? What else did UniCredit have in store? They frantically tried to reach their government contacts at the Federal Financial Agency over midnight and in the early morning, to no avail (they were bureaucrats, not investment bankers. Bureaucrats sleep at night.). Goldman Sachs, a traditional advisor to Commerzbank, smelled big trouble and immediately pulled back from the block sale. If things got nasty, they were going to face a huge conflict of interest.

More bad news arrived in the morning, September 11. UniCredit had not only acquired the government’s share block but had covertly been buying Commerzbank in the stock market as well, another 4.5%, so overnight they owned 9% of the bank. Nobody had noticed their buying. Both the investment banks and the German government sleepwalked through the sale. UniCredit pulled off a power move which will most likely become a case study in business schools.

On the other side of the fence, the government was so badly prepared it even received a scolding from EU leadership for stumbling through the re-privatization, as the process was damaging for capital markets.

Commerzbank itself was frozen stiff with fear. CFO Bettina Orlopp forced a smile into newsroom cameras and said that the government better wait before putting the remaining stake (12%) up for sale. Well, that insight didn’t really require a PhD in game theory.

UniCredit’s CEO Andrea Orcel, a hard-boiled dealmaker, now is in negotiations with the government for a takeover. With that strike, he would gain control over four of the erstwhile five large private-sector banks.

As bad as the Commerzbank episode looks, it is just a portent of much worse to come.

The China car blitz

China has launched an unprecedented export offensive with cars. Exports have been rising strongly for three years but received additional stimulus.

(Exports of leading car producers, Sept. 2023. Source: Financial Times)

China has been an export-oriented economy for decades, but now is facing a new environment. Because of the crash in its real estate sector, domestic demand is in free fall. China is therefore stepping up exports. In 2024, most likely the country will export six million cars, or 500,000 a month on average.

China has built competitive advantages in key areas of the production. It produces around one billion tonnes of steel per year, just as much as the rest of the world combined1. Much of it was used for domestic construction in the past, but as construction has ground to a halt, it is being pushed into exports – either directly (2023 exports were up 35% vs. the previous year, creating another global trade dispute) or manufactured in cars.

China has also developed control over key resources for battery production, with a global production share of 60% or more for nickel and lithium.

(Source: Goldman Sachs Research, Oct. 2023)

Car manufacturers in Europe are struggling already without the Chinese competition. In particular, the transition to EVs has all but lost momentum. The German government once again delivered a lesson in how-not-to-do it.

In its crusade for a net-zero economy (which is getting lonelier by the day) the government promised lavish subsidies for buyers – 4,500 euros for cars selling for up to 40,000 euros. Funds for the subsidies came from the Climate-and-Transformation-Fund, a vehicle to incentivize purchases of EVs, heat pumps, and other projects. But the country’s federal constitutional court ruled at the end of last year that a large part of the fund’s financing violated constitutional deficit limits. The subsidies for EVs ran out, and sales of cars collapsed.

In 2019, in another pompous comment, Germany’s minister of the economy said that “if Volkswagen can’t offer an EV for under 20,000 euros by 2025, then I’m afraid you’ll fail.” But at the same time, he increased costs for manufacturers. In 2022, he shut down the countries’ nuclear power plants despite escalating energy prices. Nuclear was the cheapest producer and would have put a cap on prices. And in a new bizarre plan, minister Habeck wants producers to align their production to the weather.

As sales of the German car companies slumped, their shares prices underperformed strongly. The leading German stock market index is up 20% in a year, while the car companies are down between 18% (Mercedes) and 24% (BMW).

With weakness in their product portfolios, low stock market prices, and declining sales they are turning into prime takeover candidates.

Each of those companies could provide huge leverage for Chinese car producers:

Distribution network: The key missing ingredient for Chinese car companies is distribution. Several companies literally sent their container ships (some of which they own) to European ports and dumped thousands of cars – but nobody was there to pick them up and sell them. Acquiring a German company would give the Chinese immediate access to a global distribution and service network.

Technology: The Chinese would not only get the most advanced ICE technology, but also trade secrets for safety (structural integrity of passenger cabins in crash scenarios and active/ passive safety features. Let’s not forget it was Mercedes-Benz who first built ABS and airbags into cars, both of them revolutionary technologies) and car longevity in different climate zones - another major concern of buyers.

Tariffs: The EU has announced tariffs on Chinese car imports (much like the U.S.). EU commissioner Valdis Dombrovskis is now in consultations with Chinese commerce minister Wang Wentao to resolve the dispute over Chinese subsidies.

But it would be immensely more difficult, if not impossible, to impose tariffs on a European company, even if owned by a Chinese company.

Who’s the most vulnerable target?

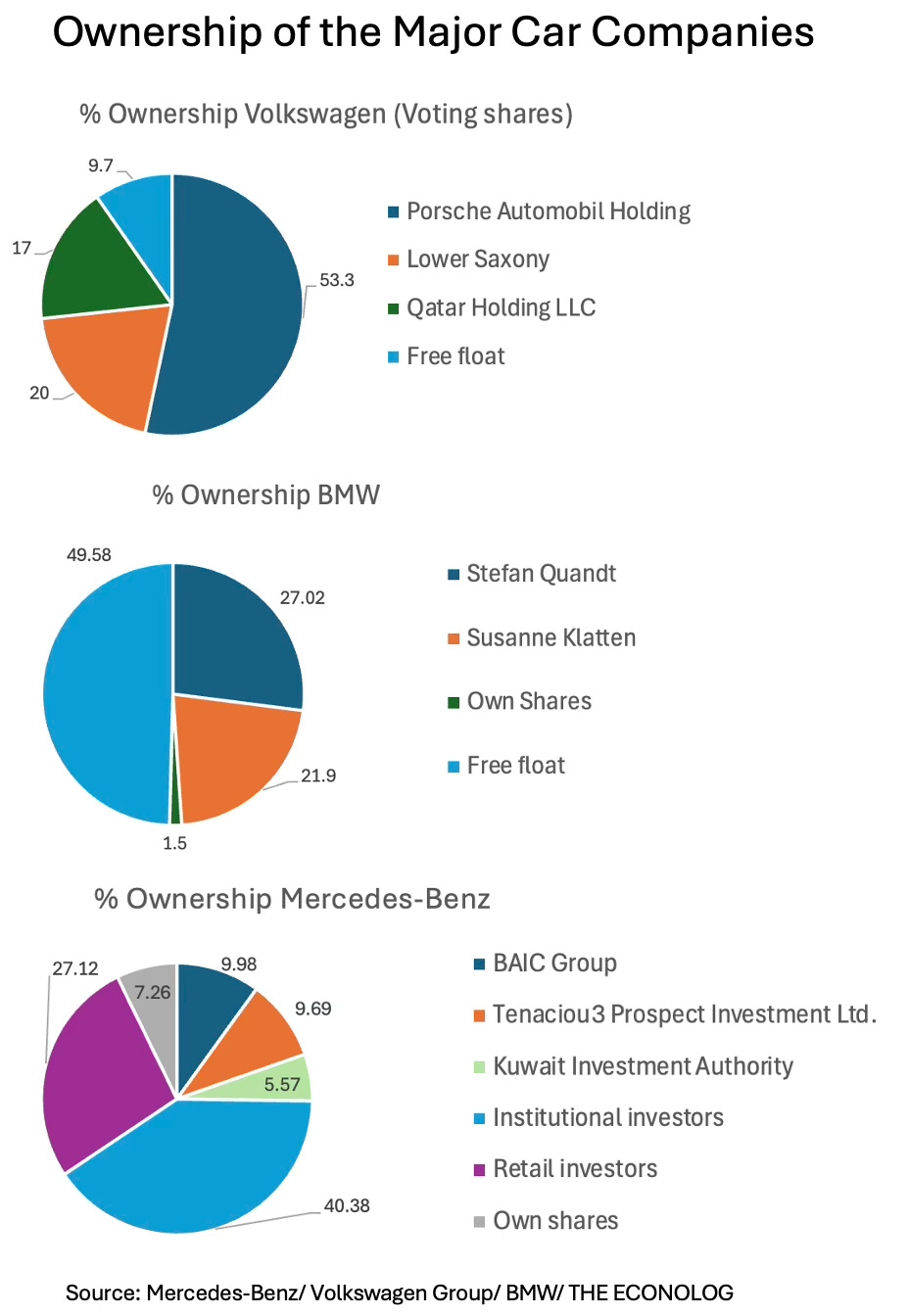

Unexpectedly, there are significant differences in the shareholder structures of the German car industries. Let’s take a quick look.

Turns out, Volkswagen has a protective shareholder structure. German state Lower Saxony owns 20% of voting shares, and Porsche Holding more than 50% (a leftover from a failed acquisition attempt in 2005-2009).

BMW is still family-owned (Imagine the days when dividends are paid). A hostile acquirer won’t get above the 50% threshold.

Mercedes-Benz: A fragmented shareholder base, making the company vulnerable to a hostile attack. The largest shareholder is BAIC, the Beijing Automotive Group (!!), which considers itself “the backbone enterprise of China auto industry”2. BAIC is the transformation vehicle for China’s car industry and provides the following services: independent research and development, industrial chain construction, opening to the outside world, transformation mechanism, joint venture and cooperation, technology introduction and application of social capital3.

In the current environment, this alone should have alarm bells ringing at the highest company and government levels.

The second-largest shareholder is Tenaciou3, an investment company controlled by Li Shufu. Li Shufu also is the founder and chairman of Geely Holding, one of the largest Chinese car companies. Obviously, both shareholders remained just below 10% to avoid regulatory declarations about the purpose of their investments.

The German government believes that while its economic transition plan is painful, the country can run through it just biting its teeth together and grinding on. What it doesn’t realize is that it weakens its corporation and makes them easy prey for foreign competitors. Global companies don’t have to play by Germany’s rules. They will take over German companies, take the technology home and employment to the cheapest cost base.

Western governments and corporations still underestimate the Chinese strategic target to dominate key industries. The current, largely self-inflicted weakness of German companies provides a unique opportunity to act. Both the German government and companies have shown in the Commerzbank debacle they are unprepared and easily pushed into the defense.

Robert Habeck, minister of the economy, has called for a crisis summit of the car industry on Monday, September 23rd. I have little doubt he will focus on employment guarantees at Volkswagen, which plans to shut down a few factories, and potentially some sales subsidies – regressive ideas of an industrial age long gone by, and ignoring the transition of the industry under global forces.

Let me know what you think!

All the best,

John

Dear readers,

This was another pretty research-intensive posting. I hope it was helpful for you! Please drop me a like or comment, and if you haven’t subscribed, please sign up! It really helps this newsletter keep going.

Many thanks!

Source: The Economist, 2024-09-17

Source: BAIC website

Source: BAIC website

Like I forecast, UniCredit increased its stake in Commerzbank even more. Today the bank acquired derivatives to collect an additional 11.5% of Commerzbank shares, while the attention of the minister of the economy, Robert Habeck, is fully absorbed by the car industry’s emergency meeting (another self-inflicted drama). UniCredit outmaneuvers the German government left and right.

Great analysis. Habeck has shown countless times that he is missing the big picture stuff. I agree that Mercedes is the biggest candidate for a takeover. You just need some institutional investors to sell their stake and “d Käs isch butzt” as the Swabian’s used to say.