Another BRIC in the Wall

They are building a fort to challenge the dollar’s dominance. Their chances are slimmer, but the opportunity is greater than they think.

Dear readers,

A few weeks ago, the most influential economic agreement of all times celebrated its 50th anniversary. The economic order which was created that time is under attack today. What are the chances of success of that attack? The events 50 years ago provide a helpful framework to assess.

It’s the longest posting I’ve written so far – I spent a lot of time on research and crunching IMF data. Hope it is entertaining and useful! Please leave me a like, comment, and please subscribe if you haven’t done so. It keeps the newsletter going.

Just over fifty years ago, on June 9th, 1974, U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger and Saudi Prince Fahd bin Abdulaziz Al Saud concluded an inconspicuous agreement between the USA and Saudi Arabia, setting up the “Joint Commission on Economic Cooperation”.

The language in the contract was vague. The commission was supposed to foster closer political ties between the two countries, assist Saudi industrialization, and facilitate the flow of American goods, services, and technology to Saudi Arabia.

The real targets of the partnership were not spelled out: Saudi Arabia was expected to produce enough oil to stabilize world demand “at stable, and hopefully lower prices”1; in turn, the U.S. would provide Saudi Arabia with suitable investment opportunities for oil sales proceeds.

1973 - probably the most pivotal year in economic history

At the time the commission was established, in the early 1970s, the world economy was in transition. It left an era of stability which had been established at the end of the Second World War, and which enabled incredibly strong economic and social progress. It was now entering a new era of volatility and uncertainty.

The transition was sparked by a perfect storm of geopolitical and economic events.

In 1973, the global system of fixed exchange rates, called the Bretton-Woods system, collapsed. The system had been launched in 1944 to prepare for rebuilding the world economy after the Second World War. At its core was a system of fixed exchange rates with the U.S. dollar as an anchor. The USD itself was tied to gold at a price of $35 per ounce of gold. To maintain that peg, the New York branch of the U.S. Federal Reserve committed to buying or selling any amount of gold at that price.

By the late 1960s, large imbalances had built in the exchange rate system. The U.S. economy was growing at red-hot pace and received additional stimulus from governmental spending for the Vietnam war, leading to excess demand for foreign products and currencies, in particular the D-mark, West Germany’s currency. To maintain the exchange rate, following the Bretton-Woods contracts, the German Bundesbank kept buying excess dollars, which however increased the German money supply and became a threat to price stability. Several countries had already adjusted their exchange rates since 1967. In February 1973, Japan and European countries including Germany decided to cancel the peg to the dollar. It marked the end of the global system of fixed exchange rates and stability in currency markets.

Almost at the same time, the U.S. made significant changes in its energy strategy. The U.S. had operated an oil quota system since 1959 to protect domestic oil producers from cheap foreign oil. The quota system limited the amount of oil which could be imported into the U.S. to keep imports below 10-12% of total consumption. Obviously, this had the effect of keeping domestic prices above global levels, but the U.S. government pursued a strategic target: it wanted to make sure the U.S. maintained a robust domestic oil industry and didn’t become overly dependent on global markets.

But the system backfired. It created a bureaucratic monster of loopholes and exceptions, endless fights over allocations, and it pitted politicians from oil-consuming states against independent oil companies. Worst of all, the system failed to generate enough domestic supply to keep up with rapidly rising demand. The term “energy crisis” entered the language and public consciousness. Saudi Arabia was becoming a key supplier: imports from Saudi Arabia jumped from 3.2 million barrels a day in 1970 to 6.2 million in 1973.

In the end, President Nixon declared in April 1973 he was abolishing the quota system to free up imports and remove a stranglehold over American industry. However, the economic relief didn’t last long.

Right at the time the Yom Kippur/ October war in the Middle East started, OPEC members were meeting in Vienna, home to the OPEC headquarters, to discuss an oil price increase. The OPEC members were dissatisfied with their share in oil product sales. Because of the huge markup in prices for consumers due to taxes, governments in consumer countries made more money from oil, OPEC argued, than producer countries. Western oil companies offered a 15% price increase in crude oil; the OPEC members wanted 100%.

The atmosphere at the meeting deteriorated rapidly when the U.S. started supporting Israel, which was close to faltering in the war, with military supplies. Saudi Arabia’s King Faisal sent a letter to U.S. President Nixon, saying that relations with the U.S. would become only “lukewarm” if the U.S. continued sending aid to Israel. When Nixon proposed a $2.2 billion aid package three days later, Saudi Arabia decided to cut off all oil shipments to the U.S. Other Arab states followed suit. The genie was out of the bottle. Oil prices started escalating.

(After decades of stability, oil prices escalated from October 1973.)

In just one year, two key pillars of international cooperation and economic stability had collapsed: the global system of fixed exchange rates, and the reliable supply of oil at a fixed price. It created a huge vulnerability for the U.S., which was by far the largest economy in the world and the largest consumer of oil. Domestic production peaked in 1970 at just above 10 million barrels a day. By June 1974 it had dropped already to well below 9 million. As energy consumption increases in line with economic growth, a gap was opening between domestic demand and supply which policymakers understood was bound to get only worse.

Got bonds?

The general agreement on the “Joint Commission on Economic Cooperation” soon received more meat to the bones. Just one month later, in July 1974, Treasury Secretary William Simon went on a roadshow in the Middle East with a four-day stop in Jeddah, a coastal city of Saudi Arabia. Simon had previously been a senior partner and head of the treasury trading desk at Salomon Brothers, a Wall Street investment bank which was quickly becoming the leading firm of that time specifically because of its bond trading capabilities.

Simon had a bond deal for the Saudis: now that oil was trading at more than three times its historic price, and the U.S. was picking up millions of barrels a day, surely the Saudis were looking for a place to invest their hard-earned dollars? Skilled salesperson that he was, he persuaded Saudi Arabia to put much of its petrodollars back into U.S. treasury bonds, in addition to its vast purchases of U.S. military equipment.

There was one problem though. Relationships with the U.S. were still not exactly well received in the Middle East, therefore King Faisal insisted that any kind of cooperation must be kept secret. Last thing he wanted was to be publicly caught financing the archenemy of many of his neighbors in the region.

Again, the skills of ex-banker William Simon proved helpful. Treasury bonds are usually auctioned off in competitive bidding processes, with certain limits for bidders. Simon created “add-on” sales for Saudi Arabia, bypassing the standard auction process and keeping the buyer secret2.

Saudi Arabia picked up large quantities of U.S. government debt this way, accumulating an astonishing 20% of all treasuries held abroad already by 1977. To provide additional cover for the transactions, the Treasury Department, which issues monthly reports about ownership of bonds among other statistics, hid Saudi Arabia’s stake in a line item generically labelled “oil exporters”.

The interconnectedness among the U.S., Saudi Arabia, oil, and the dollar soon exceeded the wildest expectations. In March 1979, the “U.S.-Saudi Arabian Joint Commission on Economic Cooperation”, the formal entity launched in June 1974, reported on the status of projects and development assistance. It listed sixteen projects (remarkably, they already included solar energy research, the second-largest project) with an accumulated, combined investment volume of $776 million - not bad. But the backdoor Jeddah agreement (July 1974) generated a business volume of potentially up to $2 billion a month.

While there was no explicit restriction for Saudi Arabia to sell oil to other countries in other currencies, the size and weight of the U.S. relationship, combining the largest consumer with the largest producer and exporter, made the dollar the de-facto standard for international transactions for oil but also for other commodities. This meant that all buyers of those commodities needed currency reserves to pay for their purchases. The world economy transitioned from a thirty-year era in which the dollar was an administrative lead currency, as the anchor in the Bretton-Woods system, to a new era in which the dollar became the economic, global reserve currency.

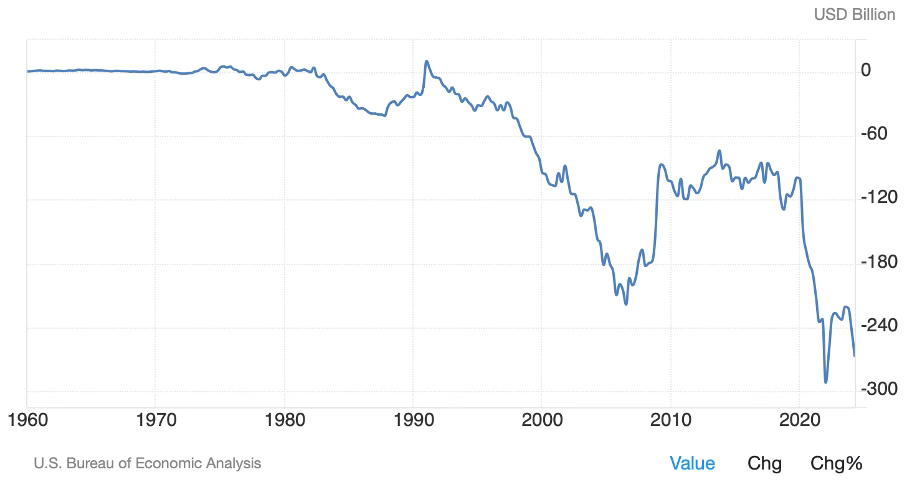

For the U.S., the reserve currency status became hugely beneficial. The only meaningful way to hold the enormous amounts of money required for international transactions is in the form of bonds. Treasury bonds therefore became the de-facto standard backing global payments. When the Treasury issued bonds to global buyers, many of the lenders wouldn’t even ask their money back from the Treasury (in practice, they simply replaced maturing bonds with new issues) – they needed treasury bonds as a vehicle for dollar reserves. U.S. borrowers therefore could, to some degree, raise money and spend for free. The larger global trade volumes in dollars were, the larger was the need for currency reserves and dollar bonds. Little wonder the U.S. current account, which measures trade flows (plus investment income and foreign workers’ remittances), soon turned decidedly negative.

Not surprisingly, other countries and economic regions wanted to have a piece of that action as well.

The U.S. thwarted an attempt of European countries in the early 2000s, but now a more serious contender is building a long-term strategy to replace the dollar: the BRICS countries under the lead of China.

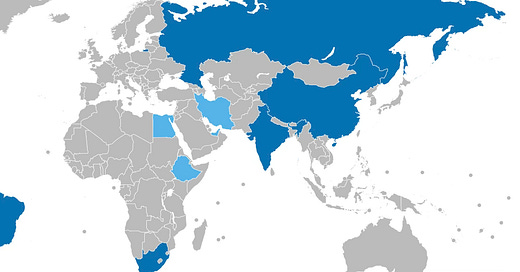

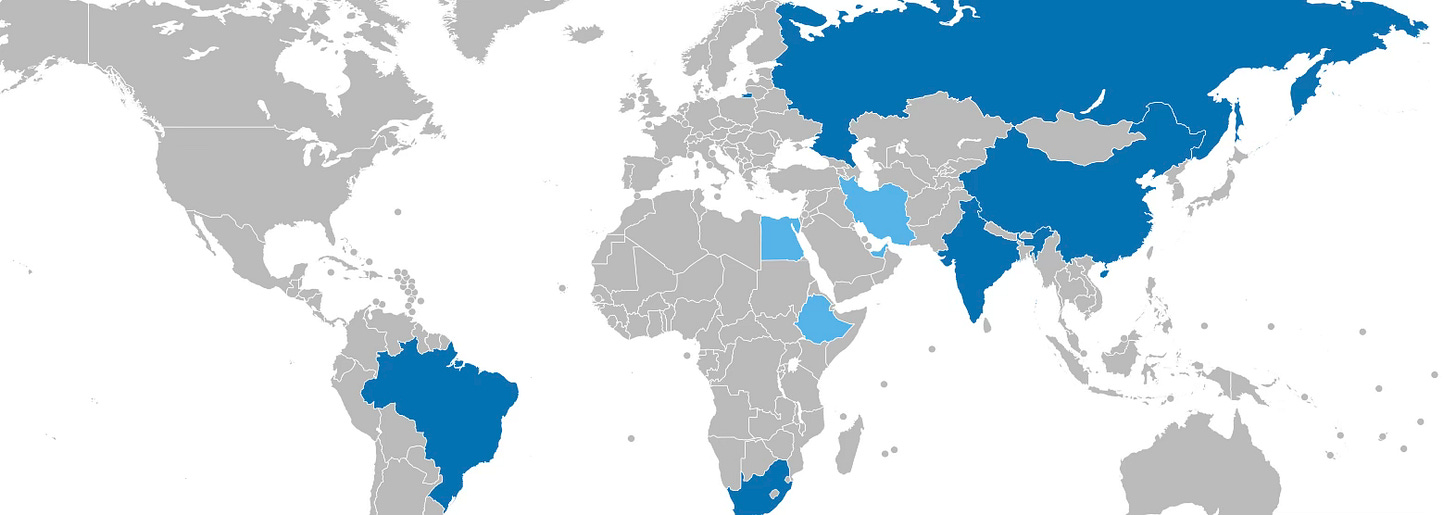

The term BRICS was originally coined in the early 2000s to market a new investment thesis. It referred to emerging countries which shared a few but not many characteristics – they were large, growing strongly, and ambitious: Brazil, Russia, India, and China. It was an informal term initially, but the association soon established diplomatic contacts, closer cooperation, and a calendar of regular meetings. It quickly added another member, South Africa, in 2010, and most recently added Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, and the UAE.

The strategy of the BRICS+ countries is clear: build a counterweight to a unipolar world with the dollar as the global reserve currency. The BRICS countries represent a larger share of world GDP (on a purchasing-power basis) than the G7, have a much larger population, and have set up their own institutional framework:

The New Development Bank (NDB), headquartered in Shanghai, which is supposed to finance infrastructure and development projects in BRICS countries and other emerging markets – obviously the equivalent of the World Bank.

The Contingent Reserve Arrangement, to provide support to member states in economic crises – the equivalent of the IMF.

Has the BRICS system become a threat to the dollar system ? China is already the world’s second-largest economy. Considering the size of its population, roughly four times of the U.S., it’s just a matter of time until China eclipses the U.S. But can China leverage its sheer size and replace the dollar in the financial economy?

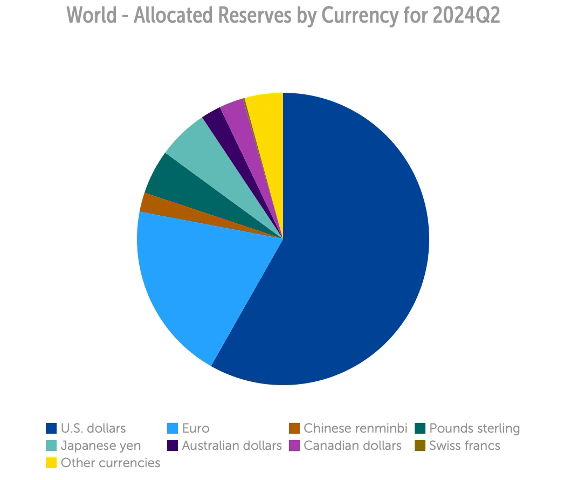

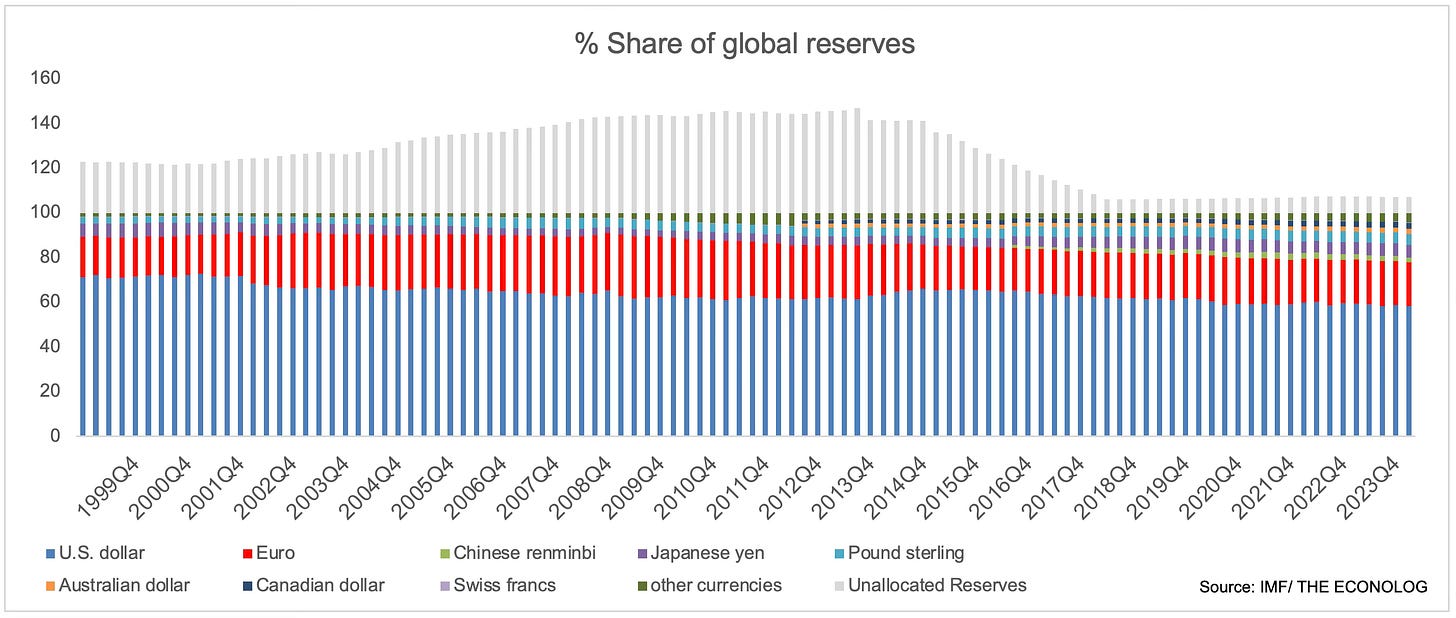

(Global reserves by currency, Q2 2024. Source: IMF)

The share of yuan in global trade (transactions) has increased to almost 6% at the end of 2023; China has set up swap lines with around 40 central banks around the world, and foreign companies tap China’s markets to raise money in panda bonds (Shanghai) and dim sum bonds (Hong Kong).

Isolated success stories, or progress in a structured approach?

Here’s what makes a currency desirable for reserve purposes:

Ample supply and liquidity: This is an area where China has made most progress, building swap lines with other central banks to give them access to yuan. Already by the end of last year, China negotiated bilateral swap lines with 39 central banks for a combined value of $550 billion.

Stability: limited fluctuations against other currencies; it must function as a store of value, so holders of the currency don’t lose purchasing power due to price depreciations. This is what China is most worried about, and it’s the reason why the country has hesitated to further liberalize domestic financial markets.

Convertibility: it should be easy to exchange the trade currency into other currencies. If Saudi Arabia or the UAE sell their oil to China for yuan, what will they do with all the yuan they receive? They need other currencies for their global purchases, even if China is their largest trading partner. However, the yuan is not freely convertible, which is one of the biggest obstacles towards becoming a widely accepted trade currency.

Deep financial markets: for central banking reserves, the only suitable way to hold large amounts of foreign currency is in the form of bonds. A reserve currency needs large and liquid financial markets. This is China’s biggest weakness at the moment. Access to markets is still cumbersome, bureaucratic, and unpredictable. The Chinese government routinely interferes in markets, e.g. restricting security sales, preventing investors from repatriating sales proceeds, etc.

Despite the size of China’s economy, global investors have hesitated to build yuan reserves. Even though the share of U.S. dollar reserves has been declining for many years, the Chinese renminbi/ yuan has not been able to catch up. In fact, its share has actually decreased over the last two years. Over the last five years, the share of reserves of much smaller countries like Australia or Canada has increased more than twice as much (Australia) or more than three times as much (Canada) as China’s.

The U.S. laid the roots for the dollar hegemony in a period of radical changes in the world economy, the collapse of fixed currency exchange rates and fixed oil prices. While the dollar share of reserve holdings has been declining, the process took place at glacial speed, and there is no clear frontrunner for substitution. Both the euro and the yuan are actually in retreat, the latter from a small base. It seems that global central banks are diversifying their reserve holdings with a preference for countries with robust financial markets and sound, orthodox economic and financial policies, like Australia, Canada, European Nordic countries, or South Korea. China, in contrast, has not been able to leverage its enormous economic size into a larger weight in the financial economy.

The road map for China in principle is pretty obvious: liberalize domestic capital markets and open them up for international investors; however, it runs exactly against the CCP’s dogma of central control over all aspects of China’s economy and society. This is all the more regrettable, from China’s perspective, because an opportunity may open up sooner than they expect.

The main threat, paradoxically, for the U.S. dollar comes from inside the U.S.: the unparalleled and uncontrolled increase of government debt. A collapse of U.S. debt markets might provide exactly the environment of chaos and disruption which enabled to dollar to gain dominance in the past, and which a challenger needs today.

Let me know what you think!

All the best,

John

The Assistant Secretary of State for Near Eastern and South Asian Affairs in the House Committee on Foreign Affairs, August 7th, 1974: “In helping the Saudis to find a way to invest their larger and growing financial reserves, we will give them added incentive to continue to produce oil in the quantities needed to meet world demand at stable, and hopefully lower, price levels”.

It probably wasn’t the first time and certainly not the last time that Salomon bankers rigged the auction process. In 1990, the bank was caught submitting excess bids to generate additional trading revenues, a Wall Street scandal from which the bank never recovered, and which eventually led to its demise.

Excellent piece! Fascinating.

Fascinating history of the rise of USD as reserve currency! I don’t believe its reserve currency status is threatened even with the gigantic debt burden the US has, because there is no real substitution. The worry for large debt burden is yield premium and higher long-term inflation. Thanks for writing!